Dr Yusuf Abdallah Contact

FY2 Doctor, Wye Valley NHS Trust, UK

Mr Simon N Madge

Consultant Ophthalmologist, Wye Valley NHS Trust, UK

Abstract

Varicella-zoster virus commonly causes shingles in the elderly population. A classic presentation of a blistering rash preceded by neuropathic pain in the affected dermatome is well-recognised amongst doctors. However, atypical presentations may also occur which require astute knowledge of the distribution pattern of the nerve affected and a thorough history and systemic examination to allow diagnosis. We present a rare case of maxillary division shingles with ocular manifestations in a 71-year-old woman post cataract operation.

Background

Herpes Zoster (also known as shingles) is a common condition occurring due to reactivation of the dormant varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in dorsal root ganglia or extramedullary cranial nerve ganglia [1]. The primary infection, varicella (chickenpox), is very common amongst children while Herpes Zoster occurs in 3-5% of the population, primarily in the elderly and immunosuppressed. Most infections affect the T3 to L3 dermatomes but 13-15% of patients present with infections involving any of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve [1,2]. The ophthalmic division is most commonly affected out of the three divisions [3]. However, not all shingles affecting the eye stems from ophthalmic division shingles as the case will illustrate. An outbreak is classically characterized by severe pain or alteration in sensation in the affected nerve’s distribution 3-5 days prior to eruption of vesicles on the skin or mucous membranes. This reactivation is postulated to be due to temporary compromises in host defenses however other factors such as age, physical trauma, psychological stress, malignancy and generalized immunocompromised states are thought to be predisposing factors [3].

Case presentation

This article presents the case of a 71-year-old lady who presented with left eye pain and redness following recent cataract surgery in the same eye. She contacted her ophthalmologist by telephone just under two weeks post-op to report having sudden onset left eye pain for several hours in addition to tingling on her left cheek developing over the last two days. She was seen in clinic the same day.

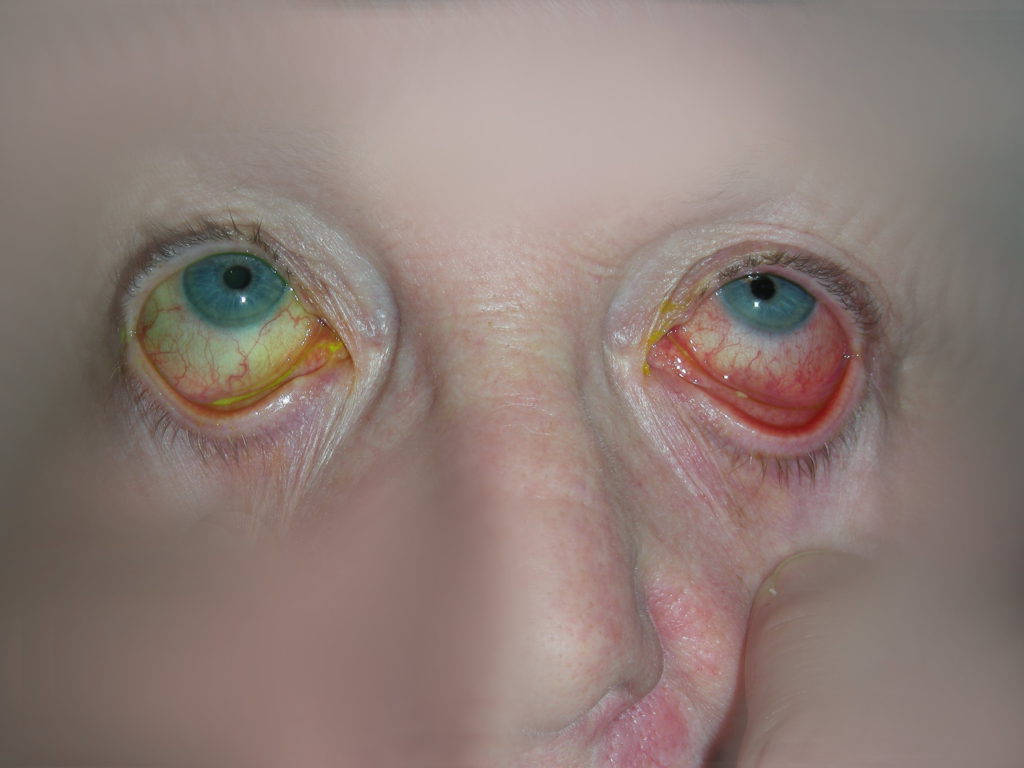

On examination, she was found to have painful blisters and vesicles on her left lower inner eyelid, the base of her left nasal ala in addition to an ulcer within her left upper gingival fornix (figures 1 and 2). The left conjunctiva was injected but bearing no signs of scleritis or dacryoadenitis. Her vision in the left eye remained unaffected at 6/6, as it was one-week post-op. She had no previous past medical or ocular history of note and had not experienced shingles in the past. The impression at the time was that of maxillary division (V2) shingles. She was started on a course of high dose Acyclovir and follow up was arranged. She was seen 3 days later, and examination demonstrated further evolution of her shingles which was, however, much less sore now. She was seen again in two weeks and her shingles appeared to have recovered (figure 3). Furthermore, the vision in her left eye improved to 6/5 and the patient was keen to proceed to right-sided cataract surgery.

Figure 3 – Patient recovered

Figure 2 – Ulcer within left upper gingival fornix

Figure 1b – Blisters on left lower inner eyelid

Figure 1a – Blister at base of left nasal ala

Discussion

Varicella zoster virus can cause both primary and recurrent infections. Chicken pox, the primary infection, presents with gingivostomatitis and a generalized viral prodrome with full recovery afterwards and the virus remaining dormant in sensory ganglia. The reactivation is noted to be infectious to individuals who have not been in contact with the virus. With a lifetime incidence of 10-20% and prevalence of 3-5%, it is a common condition and carries significant morbidity if not treated appropriately. The commonest chronic complication is pain along the affected areas after the resolution of the acute stage, known as post herpetic neuralgia (PNH). This is described to last 1-3 months after the acute phase but can last for years [3]. The incidence increases in immunocompromised patients especially those with HIV as well as with age, the highest being amongst people age 60-90 [3].

VZV classically presents with paraesthesia and/or pain in the affected dermatome preceding a vesicular eruption in the affected mucosa or skin. A viral prodrome of malaise and fever has also been described. VZV affecting the eye often stems from ophthalmic division disease leading to cutaneous manifestations in its dermatomal distribution in addition to conjunctivitis, keratitis, and uveitis. When vesicles are seen on the tip of the nose in a patient suspected to have shingles, this raises the suspicion of nasociliary nerve involvement (Hutchinson’s sign) and strongly predicts the involvement of the eye. Furthermore, involvement of the ciliary ganglion may give rise to a small pupil that accommodates appropriately but does not constrict when exposed to light (Argyll Robertson pupil). These cases can be acutely complicated by episcleritis, scleritis, acute retinal necrosis, cranial nerve involvement, optic nerve palsies and meningoencephalitis. Long term ocular complications include cataract, glaucoma, and corneal scarring with subsequent vision loss [4,5,6,7].

Despite this classic presentation, VZV can present in many other modes [8]. As highlighted by our case, not all VZV affecting the eye is due to ophthalmic division disease but the maxillary division can also be implicated. This is rationalized by the conjunctival supply from the maxillary division, via its infraorbital nerve, where it supplies the medial portion of the inferior forniceal and palpebral conjunctiva [9]. Maxillary division disease often presents with both intraoral and facial vesicles. Intraorally, these rupture to form painful ulcers. On the skin and lips, the same rupturing of vesicles results in erosions covered by pseudomembranes and haemorrhagic crusts. The lesions evolve over a week and settle within the second to third week of infection. Maxillary division shingles can be complicated by devitalization of teeth and necrosis of underlying bone [1,3]. Consequently, these patients often present to oral health clinicians as the eye is not commonly implicated in maxillary division Herpes Zoster or at least it is not the organ of main presenting complaint.

Treatment is centered around early initiation of antiviral drugs and analgesics. It aims to reduce pain, facilitate rapid healing, and avoid complications. It is widely agreed that anti-viral treatment should be started within 72 hours of rash onset as this early initiation is associated with a reduction in further incidence and complications such as PNH. Oral anti-viral drugs are often sufficient but more severe cases may necessitate admission and intravenous administration. The use of corticosteroids is described in certain VZV infections such as Ramsay Hunt and with ocular complications and may be associated with improved outcome in select cases [10].

Learning points

- Red eye complaints are common, and a wide differential must always be considered. Lateral thinking will ensure important diagnoses are not missed or masked by confounders.

- Shingles affecting the eye can arise from ophthalmic and, much more rarely, maxillary nerve division disease.

- Shingles affecting the eye can present and coincide with other ophthalmological history/procedures.

- A systematic approach to new patients is important as to not miss diagnoses.

- Aciclovir is the mainstay of treatment and the patient must be followed up by an ophthalmologist to monitor progress.

References

1. Wadhawan R, Luthra K, Reddy Y, Singh M, Jha J, Solanki G. Herpes Zoster of Right Maxillary Division of Trigeminal Nerve Along with Oral Manifestations in a 46 Year Old Male. International Journal Of Advanced Biological Research [Internet]. 2015 [cited 18 July 2020];5(3):281-284. Available from: https://www.scienceandnature.org/IJABR_Vol5(3)2015/IJABR_V5(3)15-17CS.pdf

2. EP M, MJ T. Herpes zoster of the trigeminal nerve: the dentist’s role in diagnosis and management [Internet]. PubMed. 1994 [cited 18 July 2020]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8004523/

3. Hasan S, Ishrat khan N, Nakeb A, Tarranum F. Herpes zoster with oro-facial involvement – Report of a case and detailed review of literature. Indian Journal of Dentistry. 2012;3(2):94-101.

4. Womack L, Liesegang T. Complications of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1983;101(1):42-45.

5. Rook A, Griffiths C. Rook’s Textbook of dermatology. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell; 2016.

6. Yawn B, Wollan P, St. Sauver J, Butterfield L. Herpes Zoster Eye Complications: Rates and Trends. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2013;88(6):562-570.

7. Tran K, Falcone M, Choi D, Goldhardt R, Karp C, Davis J et al. Epidemiology of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1469-1475.

8. Wollina U. Variations in herpes zoster manifestation. Indian Journal of Medical Research [Internet]. 2017 [cited 18 July 2020];145(3):294-298. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5555057/

9. Forrester J. The Eye: Basic Sciences in Practice. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, London: Elsevier; 2016.

10. Koshy E, Mengting L, Kumar H, Jianbo W. Epidemiology, treatment and prevention of herpes zoster: A comprehensive review [Internet]. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venerology and Leprology. 2018 [cited 18 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.ijdvl.com/text.asp?2018/84/3/251/226945