Mohib Naseer

Introduction

Toxocariasis is an infection in humans due to Toxocara canis (T. canis) and occasionally by Toxocara cati (T. cati). These nematodes develop during the adult stage in the intestines of cats and dogs. After being ingested by humans, the larvae go through the intestinal wall, migrating via the veins into the liver and the rest of the body, where they remain as larvae. Clinically, two syndromes are described: visceral larva migrans (VLM) and ocular larva migrans (OLM) which, although presented as independent pathologies, are able to coexist.

The presumptive diagnosis of VLM or OLM is generally based on clinical signs, laboratory findings and a history of geophagia and contact with dogs. The clinical signs of toxocariasis are not specific and differential diagnoses include other parasitic diseases characterized by hypereosinophilia, such as allergic reactions, asthma, other helminthiasis (e.g., filariasis). Peripheral eosinophilia has been constantly associated with VLM but not among patients with OLM, probably due to low larva numbers (1)

Case Presentation

A previously healthy 27-year-old male presented with progressive worsening of vision, mild redness and photophobia in his left for 2 weeks. There was no significant past ocular history, no history of fever, skin rashes or upper respiratory tract infection. No recent history of travel. He has a pet dog. Clinically, the patient was alert and oriented, vital signs were stable and he was afebrile. Systemic review was unremarkable.

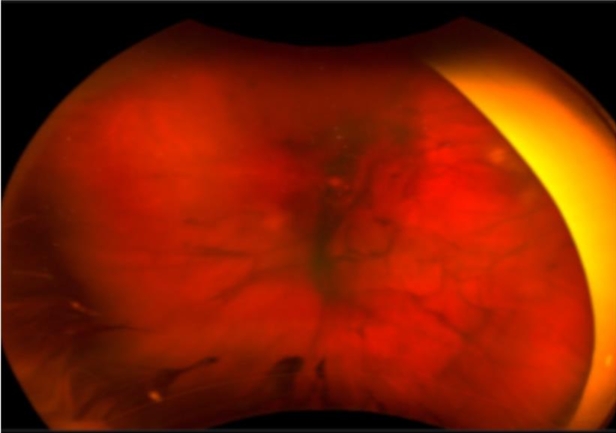

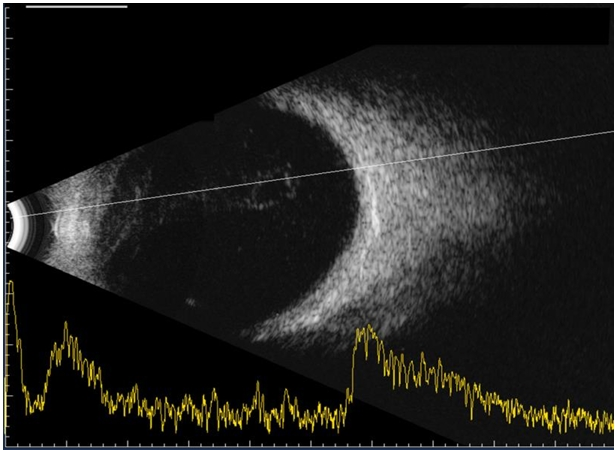

On examination, his vision was 6/6 unaided in the right eye and 1/60 unaided in the left eye. Anterior segment examination of his left eye showed mild injection, +3 AC cells, round and reactive pupil. Hazy fundal view with vitreous activity and vitreous strands and no further details visible. B-Scan ultrasonography of the left eye showed vitreous opacity and flat retina (see figure 1B). Optos fundus photos revealed vitreous opacities (see figure 1A). Examination of right eye was unremarkable.

Investigations: FBC, U&E, ESR, CRP and ACE were normal. CXR was reported normal, awaiting progress on uveitis screening. Left eye AC paracentesis was done and aqueous tap sent for bacterial culture and sensitivity, as well as viral PCR. The patient was commenced on topical steroids, oral antibiotics, antivirals and was given sub tenon steroid injection.

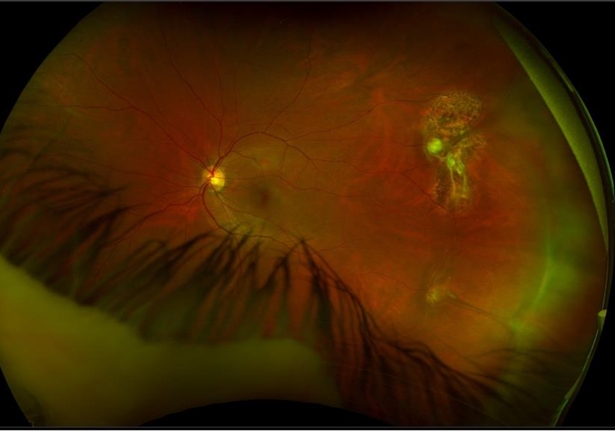

Despite 10 days of treatment the patient showed no improvement in his vision on oral and topical treatment. At this stage he was admitted for diagnostic 25-G vitrectomy, intravitreal antibiotics and amphotericin B. Following vitrectomy, his vision improved from 1/60 to 6/6 post operatively (see figure 1C).

Toxoplasma serology, herpes simplex serology, B. burgdorferi serology, VDRL for syphilis and HIV serology were negative. Microscopic examination of vitreous fluid showed predominantly chronic inflammatory infiltrate. This was negative for bacterial growth, viral, fungal , protozoal or nematode infection. Meanwhile bloods for Toxocara IgG & IgM came back positive with ELISA and Western Blot method.

After consultation with infectious diseases, the patient was commenced on Albendazole 400mg BD, Ciprofloxacin 500mg BD, Prednisolone 60mg/day and Omeprazole 40mg/day.

He remained under review following vitrectomy. On his latest follow up visit at 8 months after his first presentation his vison remained stable at 6/6 unaided in the right and 6/6 unaided in the left eye. No recurrence of intraocular inflammation was seen.

Discussion

Human infection with toxocariasis is due to accidental ingestion of infective eggs and tissue invasion of second stage T. catior T. canis larvae. It is transmitted by contaminated food or by geophagia (2). OLM usually affects older children, with a mean onset age of 7.5 years and about 80% of cases less than 16 years of age. The most common symptoms and signs are strabismus, unilateral decreased vision, leukocoria, peripheral posterior pole retinal granuloma and endophthalmitis (2). Most of the patients present with unilateral involvement (3). The major causes of visual acuity loss are: severe vitritis (52.6% of the cases), cystoid macular oedema (47.4%) and tractional retinal detachment (36.8%) (4).

Diagnosis of Ocular toxocariasis can be difficult. It is based upon clinical features confirmed by serological testing. The levels of antibodies in the serum are usually low or undetectable (1),(3) and eosinophilia is often absent in OLM. Aqueous and vitreous fluids are the best options for diagnostic sampling. Testing of ocular fluid sample did not give absolute positive result because approximately 10% of patients with clinical signs of OLM presented negative results by ELISA method (1).

The mainstay of the treatment is steroids and anthelmintics. Steroids administered either systemically or by peri ocular injection to reduce the inflammatory reaction (2),(3). Antihelminthic treatment with albendazole is the treatment of choice. Albendazole crosses the blood-brain barrier and has a proven potential for killing larval stages of toxocara in the tissues of paratenic hosts (3). Diagnostic vitrectomy is a useful intervention specially in cases of dense vitritis with unusual presentation, Or if diagnosis is not clear considering the wide verity of differentials and potential of poor visual outcome (5).

Conclusion

Diagnostic dilemmas often arise with unusual clinical presentation, persistent worsening of clinical condition, and delayed/inconclusive diagnostic work up. Aggressive approach is indicated in certain clinical situations particularly in infectious uveitis where a delay in treatment may cause poor visual outcome. Considering patients’s age unusual presentation, a diagnostic and therapeutic vitrectomy was an appropriate intervention resulting in quick visual rehabilitation and an excellent visual outcome.

The diagnosis of ocular toxocaraisis can be challenging given the relatively uncommon occurrence and presentation which varies from patient to patient.

References

1. Chieffi PP, Santos SV, Queiroz ML, Lescano SA. Human toxocariasis: contribution by Brazilian researchers. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009 Oct-Dec;51(6):301-8. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000600001.

PMID:20209265.

2. Pivetti-Pezzi P. Ocular toxocariasis. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(3):129-30. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.129. Epub 2009 Mar 19. PMID: 19319231; PMCID: PMC2659485.

3. Rubinsky-Elefant G, Hirata CE, Yamamoto JH, Ferreira MU. Human toxocariasis: diagnosis, worldwide seroprevalences and clinical expression of the systemic and ocular forms. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2010 Jan;104(1):3-23. doi: 10.1179/136485910X12607012373957. PMID: 20149289.

4. Stewart JM, Cubillan LD, Cunningham ET Jr. Prevalence, clinical features, and causes of vision loss among patients with ocular toxocariasis. Retina. 2005 Dec;25(8):1005-13. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200512000-00009. PMID: 16340531.

5. Gómez L, Rueda T, Pulido C, Sánchez-Román J. Toxocariasis ocular. A propósito de un caso (Ocular toxocariasis. A case report). Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2008 Jan;83(1):49-52. Spanish. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912008000100010. PMID: 18188795.