Virginija Vilkelyte

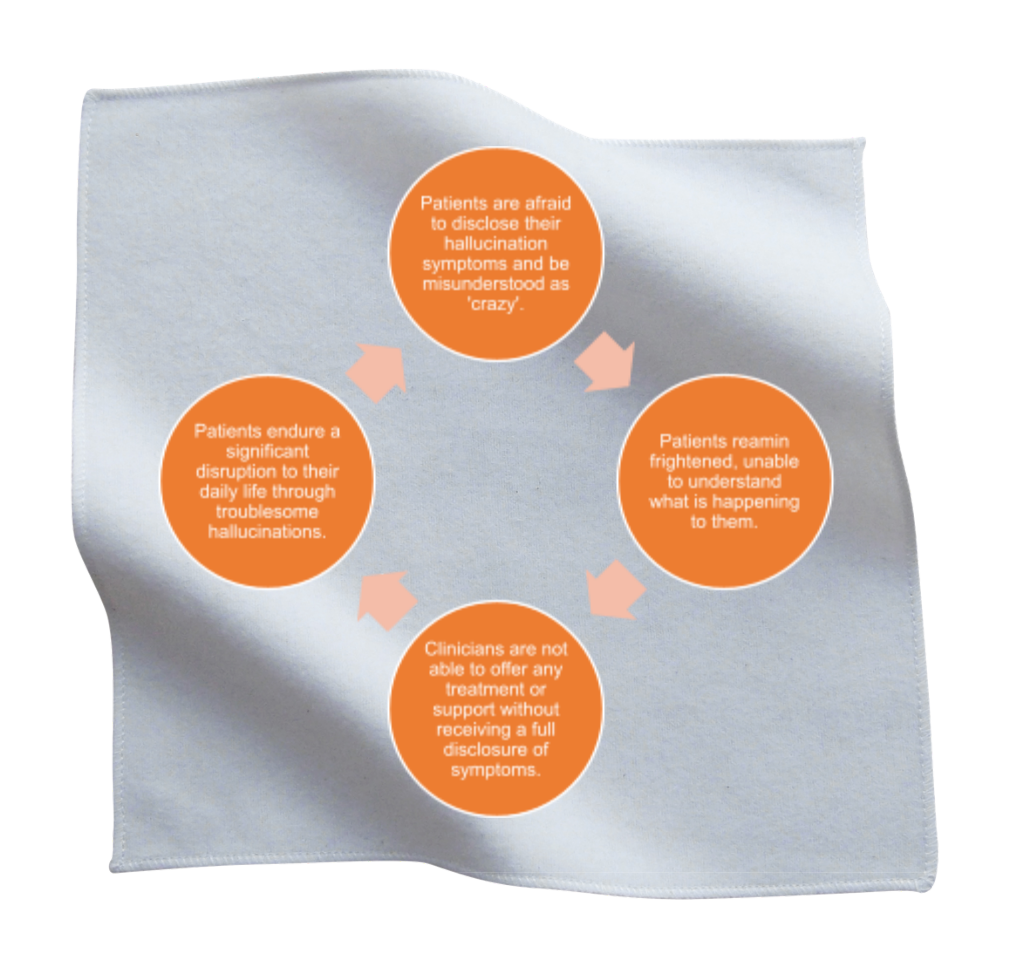

Envision yourself in a hypothetical future where you are 87 years old and residing in Geneva, Switzerland, after having led a healthy life. As you relax on your sofa one afternoon, you notice something peculiar. There is a white handkerchief with four orange circles floating in the air. This sight leaves you momentarily frightened and bewildered. How could a handkerchief be floating in space? Where did it come from, and how did it get there? You may experience a range of emotions in this scenario. Initially, you might feel compelled to call out for help, but then you might hesitate, concerned about what others might think. The fear of being misunderstood or labelled as crazy could make you feel alone and confused, even though you know that you’re the same person you’ve always been, with the same thoughts and feelings. The only thing that has changed is the presence of this unexpected handkerchief. This situation could trigger a sense of worry and isolation, which could be difficult to navigate (Figure 1).

This exact scenario happened to Charles Lulin whose only medical complaint was the presence of cataracts in both eyes (1). In 1769 Lulin’s grandson Charles Bonnet, a Swiss lawyer, naturalist, and philosopher, documented these experiences of Lulin in a book called Analytical Essays Concerning the Faculties of the Mind (English translation) (2). Then nearly two centuries later, in 1967, a French neurologist Georges de published ‘Visual hallucinations in the aged without mental deficiency’, where he coined the term Charles Bonnet Syndrome (3). In the present day the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases version 11 (4) states “Charles Bonnet syndrome, also called visual release hallucinations, refers to the experience of complex visual hallucinations in a person who has experienced partial or complete loss of vision. Hallucinations are exclusively visual, usually temporary, and unrelated to mental and behavioural disorders.” In this essay I aim to explore the importance of diagnosing CBS as well as its psychosocial impacts on patients.

The occurrence of hallucinations in individuals with CBS is believed to be caused by a phenomenon in which a decrease in visual stimuli leads to a reduction in the number of images transmitted to the brain (5). Consequently, the brain is compelled to compensate for this deficit by using stored memories to recollect past visual experiences or, in some instances, creating entirely new visual content (5). Currently, there are no established diagnostic tools used for the diagnosis of CBS, and the quality of studies testing specific medications is generally limited to a few case studies (6). Therefore, despite numerous reports of CBS symptoms, the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria and management options makes CBS a largely undiagnosed and even unknown condition to many clinicians (7).

Even amongst doctors with background knowledge of CBS, there remains a common presumption that this condition is rare. However, recent studies show that the prevalence of CBS amongst patients with visual impairment is 19.7% which means that one in five patients with low vision have CBS (8). The underdiagnosis of this condition may be attributed to the taboo surrounding it, with patients often fearing being stigmatized as “crazy.” This is a significant concern that can lead patients to withhold their symptoms from doctors, resulting in less accurate diagnoses and less awareness of the commonality of CBS.

Without a diagnosis, patients also tend to remain frightened of their symptoms, not understanding why they are experiencing hallucinations. This is very unfortunate, as sometimes even providing a name of the diagnosis and an explanation can be very reassuring to the patient. This is a very simple solution that clinicians could offer to patients, however it requires knowledge of the condition and deconstructing the taboo of the symptoms that the patients are experiencing. Once a diagnosis is made, doctors are then also able to put their focus on potentially reversing the cause of their diminished vision, if possible, which often results in the hallucinations to go away as well. In addition to this, the patients can also be referred to support groups which can also help with making the patients feel reassured.

Another important psychosocial impact of CBS is the potential disruption of daily life caused by hallucinations. While some hallucinations may be minor and more easily ignored, others can significantly interfere with a patient’s routine. For instance, patients have reported hallucinations of a brick wall, which can be particularly hazardous for older individuals, who are the primary demographic for this condition, and increase the risk of falls (9). Similarly, hallucinations of roads splitting apart can be dangerous for any patient who is moving around. These effects underscore the importance of properly diagnosing and managing CBS to improve patient safety and quality of life.

In summary, CBS is a condition that involves the experience of complex visual hallucinations in individuals who have experienced partial or complete loss of vision (1). Despite its prevalence amongst patients with visual impairment, CBS remains largely undiagnosed and even unknown to many clinicians due to the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria and management options. This underdiagnosis may be attributed to the taboo surrounding CBS, which leads patients to withhold their symptoms from doctors. Furthermore, the potential disruption to activities of daily living caused by hallucinations highlights the importance of properly diagnosing, managing, and bringing awareness to CBS.

References

1. Potts J. Charles Bonnet Syndrome: so much more than just a side effect of sight loss.

The Adv Opthalmol. 2019 Nov; 11(1):254-58.

2. Bonnet C. Essai Analytique sur les Facultés de l’Ame. Copenhaven & Geneva, 1769.

3. de Morsier G. Le Syndrome de Charles Bonnet. Ann Med Psych 1967; 128:677-702.

4. World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). Available

online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

5. Roed Rasmussen ML, Prause JU, Johnson M, et al. Phantom eye syndrome: types of visual hallucinations and related phenomena. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 25:390-3.

6. Molander S, Peters D, Singh A. Charles Bonnet syndrome: low awareness among patients with glaucoma. Ann Eye Sci. 2020; 5:30.

7. Singh A, Subhi Y, Sørensen TL. Low awareness of the Charles Bonnet syndrome in patients attending a retinal clinic. Dan Med J 2014; 61(1):4770.

8. Subhi Y, Nielsen M, Scott D, Holm L, Singh A. Prevalence of Charles Bonnet syndrome in low vision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annnals of Eye Sci. 2022 June 15; 7(1):122-25.

9. Burke W. The neural basis of Charles Bonnet hallucinations: a hypothesis. J of Neuro, Neurosurg & Psych. 2002; 73(1):535-541.