Felon Mahrous

Introduction

As the medical profession increasingly recognises the importance of diversity and inclusivity, Muslim women who wear the hijab (headscarf) continue to face unique challenges in surgical environments due to existing hospital dress codes. This article explores the intersection of religious dress practices and hospital theatre guidelines, highlighting the barriers that persist for hijabi healthcare professionals and offering practical solutions for greater inclusivity.

The representation of women in medicine continues to grow, with increasing numbers of female professionals contributing significantly across specialties. However, not all women progress through the medical career pipeline at the same rate. Muslim women who wear the hijab often face institutional and cultural challenges, particularly when hospital uniform policies conflict with their religious observance. These challenges can impede career progression and lead to difficult compromises between professional aspirations and religious identity—including in surgical specialities such as ophthalmology.

Challenges in Theatre Settings

A 2019 cross-sectional study revealed that over 50% of Muslim women reported difficulty wearing the hijab in theatre environments, and 36.5% experienced bullying or discrimination related to this issue (1). Such experiences, particularly during surgical training, can discourage Muslim women from pursuing surgical careers, thereby contributing to their under-representation in these fields. Another study conducted in 2021 found that over 75% of hijabis felt anxious about wearing the hijab in theatre and around half of them had previously been asked to remove their hijab prior to entering theatres (2). Consequently, their attention was diverted away from patient care, as they became increasingly preoccupied with the discomfort they experienced in the workplace.

Although modest dress and the wearing of the hijab are well-established and publicly recognised aspects of Muslim faith, the interpretation and implementation of dress code policies remain inconsistent across NHS Trusts. This inconsistency fosters confusion and, at times, confrontational or exclusionary workplace interactions. While NHS England updated its national uniform policy in 2020 to permit faith-compliant modifications—such as disposable theatre hijabs or the use of personal scarves meeting specific hygiene criteria—awareness and implementation remain limited.

Current Guidance and Practical Adaptations

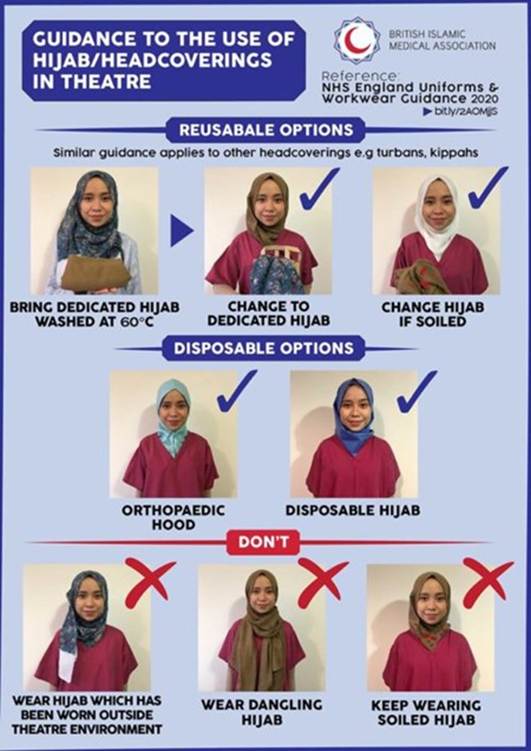

The 2020 NHS uniform policy allows staff to cover their forearms, provided sleeves can be easily pushed above the elbow for hand hygiene (3). It also permits the wearing of theatre-appropriate hijabs, which must be clean, securely fastened, and laundered at 60°C. Disposable surgical hijabs, where available, offer a practical and infection-control-compliant solution. Additionally, there is no need to wear a surgical cap over the hijab. However, these are not yet standardised across Trusts, and alternatives such as orthopaedic hoods—while effective in other disciplines—are often impractical in ophthalmology due to visibility and fit.

Image 1: Guidance to the use of hijab in theatre by BIMA Hijabs & Bare Below the Elbows Team (4)

Promoting Awareness and Institutional Support

Improved awareness is key to addressing this issue. Initiatives such as the Surgical Scarf Project have proven effective in advocating for policy implementation and supporting Muslim women in surgical fields (5). By promoting such initiatives within local hospital communities, especially in regions with less ethnic diversity, Trusts can foster a more inclusive environment.

Furthermore, embedding relevant education into early medical training—such as during medical school or foundation year inductions—can normalize discussion around religious dress and institutional policy. Simple measures, such as including a section on religious accommodations in theatre induction modules or establishing peer-support networks for staff with faith-based dress needs, could significantly reduce the burden on individual practitioners to justify or defend their attire.

Conclusion

Institutional change does not always require significant financial investment or structural overhaul. Instead, fostering awareness, consistency in policy implementation, and open communication are powerful tools in creating a supportive working environment for all healthcare professionals. Ensuring that Muslim women can maintain their religious practices while fully participating in surgical training and service delivery is not only a matter of policy—it is a matter of equity. With targeted efforts, Muslim women in ophthalmology and other surgical specialties can indeed experience the best of both worlds.

References

1. Malik A, Qureshi H, Abdul-Razakq H, Yaqoob Z, Javaid FZ, Esmail F, et al. “I decided not to go into surgery due to dress code”: a cross-sectional study within the UK investigating experiences of female Muslim medical health professionals on bare below the elbows (BBE) policy and wearing headscarves (hijabs) in theatre. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2019 Mar;9(3):e019954. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/3/e019954

2. Al-Saadi N, Al-Saadi A, Lewis S, Parvin A, Busuttil A, Bowrey D. Cut from the same cloth? The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2022 Sep;104(6):296–300.

3. Uniforms and workwear: guidance for NHS employers [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 3]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Uniforms-and-Workwear-Guidance-2-April-2020.pdf

4. BIMA | Hijab Bare Elbow Infographics | British Islamic Medical Association [Internet]. British Islamic Medical Association. 2024. Available from: https://britishima.org/advice/hijab-bare-elbow-infographics/

5. Khatun A. The Surgical Scarf Project. The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2022 Jul;104(5):250–1.