Mihai T. Bica1, Florian Balta1,2

1. Spitalul Clinic de Urgente Oftalmologice Bucuresti, Romania

2. Universitatea de Medicina si Farmacie “Carola Davila”

Introduction

Adult-onset Foveomacular Vitelliform Dystrophy (AFVD) is a rare retinal disorder characterized by the formation of vitelliform lesions in the macular region of the retina. AVMD is associated with genetic mutations in several genes, including BEST1, PRPH2, IMPG1, and IMPG2, and it is categorized within a group of conditions known as “pattern dystrophies.” While some familial cases have been reported, AFVD is predominantly sporadic in occurrence, with symptoms typically emerging in individuals between the ages of 30 and 50 [1].

Case Report

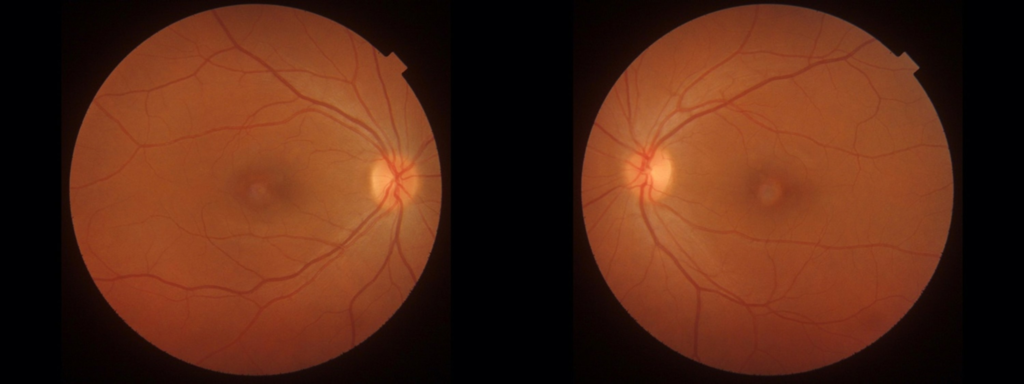

This case report presents a clinical account of a 41-year-old female patient with a two-year history of progressive bilateral reduction in visual acuity (VA) and metamorphopsias. The patient’s medical history is unremarkable, with a relevant family history limited to type II Diabetes Mellitus in her paternal grandfather. Initial evaluation at a local eye clinic yielded a diagnosis of bilateral Dry Age-related Macular Degeneration (ARMD). Best-corrected visual acuity measurements indicated 6/6 in the right eye (OD) and 6/7 in the left eye (OS), while intraocular pressure readings stood at 15 mmHg OD and 17 mmHg OS. Colour vision testing using Ishihara plates revealed no abnormalities. On Amsler grid testing, the patients reported central distortion in both eyes, more pronounced in OS. Slit lamp examination showed a normal anterior segment, but examination of the posterior pole revealed bilateral vitelliform disciform macular lesions (Figure 1).

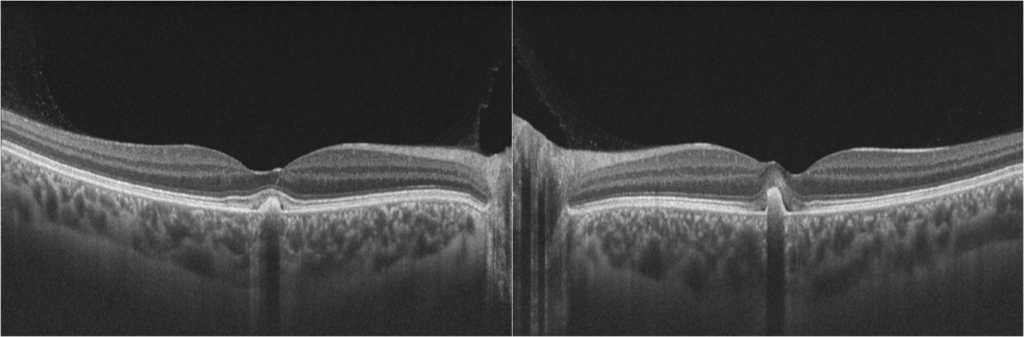

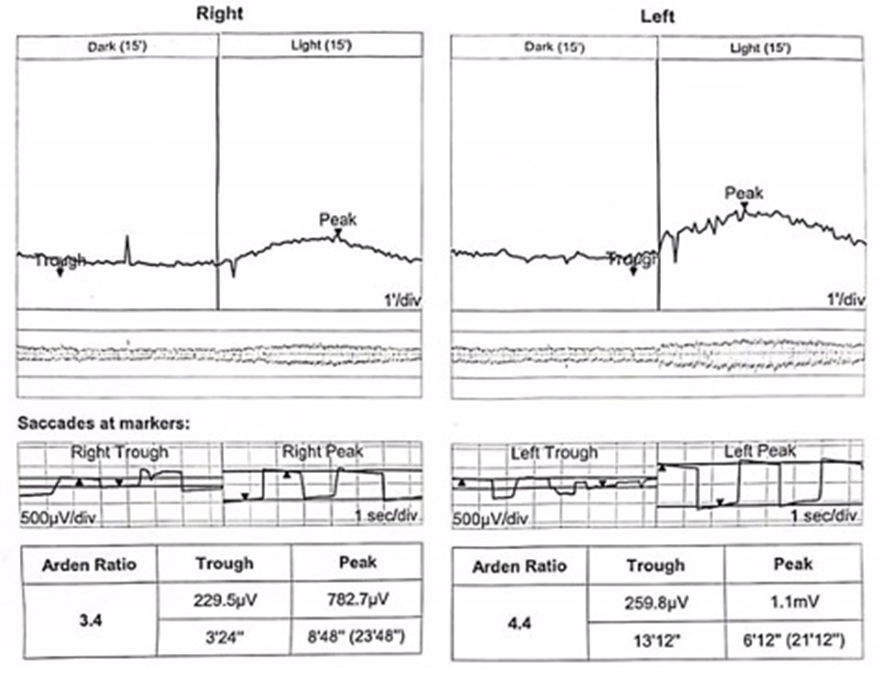

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed bilateral subretinal hyperreflective deposits with posterior signal attenuation, notably more prominent in the left eye (Figure 2). Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) imaging unveiled bilateral hyper-autofluorescent lesions surrounded by a hypo-autofluorescent halo (Figure 3). The clinical history and findings were highly suggestive of AFVD. To definitively rule out Best disease, electro-oculogram testing (EOG) was conducted, which displayed an Arden ratio exceeding 1.8 in both eyes (Figure 4), effectively excluding Best disease.

Subsequently, the diagnosis of AFVD was established, and the patient was recommended for regular 6-monthly to yearly follow-up to monitor disease progression and potential complications. At the 6-month follow-up, no disease progression was evident through clinical and OCT examination.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis in this case pivoted around AFVD, Best disease, Non-exudative ARMD and Stargardt disease. We present the arguments for and against each differential in the table below.

| Disease | Arguments “For” | Arguments “Against” |

| Best disease | Clinical appearance compatible with stage 2 (vitelliform) Central vision is affected OCT: hyperreflective homogenous dome-shaped deposits | Onset in first decades of life (usually childhood) Progressive, significant worsening of VA EOG: Arden ratio < 1.65 Family history usually present |

| Dry ARMD | History: metamorphopsias, worsening of VA FAF: hyperreflective signal in early stages due to build-up of lipofuscin | OCT: sub-RPE lipofuscin deposits Asymmetrical presentation Onset typically in older age Clinically: focal, yellow-white excrescences with a primarily central location |

| Stargardt disease | OCT: lipofuscin deposits at the level of photoreceptors and RPE At onset: can show focal hyper-autofluorescence in areas where there is a buildup of lipofuscin | Dramatic decrease in VA, poor prognosis, onset in first decades of life Inherited disease, family history Clinically: discrete pisciform flecks at RPE level, „beaten bronze” macular appearance OCT: areas of atrophy at the level of photoreceptors and RPE |

| AFVD | Bilateral, symmetrical presentation, usually in the 5th decade of life History: minor decline in VA, metamorphopsias Clinically: disciform vitelliform bilateral macular lesions OCT: hyperreflective deposits between retina and RPE FAF: central hyper-autofluorescence surrounded by hypo-autofluorescent halo EOG: normal Arden ratio > 1.8 |

AFVD belongs to the group of “pattern” dystrophies and is a rare condition with a prevalence of 1:7400 [2]. Genetic mutations associated with AFVD include peripherin 2 (PRPH2), BEST1, IMPG1, and IMPG2, although the genetic inheritance pattern remains variable, including autosomal-dominant and idiopathic forms [3]. The typical presentation of AFVD is insidious, manifesting between the fourth and sixth decades of life, often with metamorphopsias and mild VA reduction. Importantly, this condition is characterized by bilateral, symmetrical involvement, marked by subretinal lipofuscin deposition in the macular region. Imaging modalities such as OCT reveal hyperreflective subretinal deposits with intact ellipsoid zones and external limiting membranes [4]. On FAF, hyper-autofluorescent homogeneous lesions are observed [5], with potential hypofluorescence on fluorescein angiography corresponding to vitelliform lesions.

In terms of management, AFVD has no curative treatment, but it typically follows a benign and slowly progressive clinical course [6]. Some limited evidence suggests the potential benefit of carotenoid supplementation in hereditary dystrophies [7]. Familial screening was recommended for the patient. While complications are rare, they may include choroidal neovascularization and macular oedema, leading to decreased VA. As such, regular 6-12-month follow-up is advised to monitor these possible complications.

Case Highlights & Final Remarks

In conclusion, this case underscores the rare nature of AFVD, which can be challenging to diagnose and differentiate from other retinal pathologies. The importance of comprehensive assessment, integrating clinical history, slit-lamp examination, and advanced investigations such as OCT, FAF, and EOG, is highlighted. Given the diversity of retinal pathologies, a personalized approach to evaluation and management is paramount.

References

- Moss, H., Epley, K. D., Tripathy, K., Cohen, M. N., Shah, V. A., Dutra-Medeiros, M., Moura-Coelho, N., Weng, C. Y., Lim, J. I., & Gillette, T. B. (Up to Date). Best Disease and Bestrophinopathies. Eyewiki. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Best_Disease_and_Bestrophinopathies

- Nipp, G. E., Lee, T., Sarici, K., Malek, G., & Hadziahmetovic, M. (Year). Title of the Article. Frontiers in Ophthalmology, Volume(Issue), Article Number. https://doi.org/10.3389/fopht.2023.1237788

- Telander D, Small K.W. Macular Dystrophies. In S. Yanoff & J. Duker (5th edition.), Yanoff & Duker’s Ophthalmology (494-496).

- Do, P., & Ferrucci, S. (2006). Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy. Optometry, 77(4), 156-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optm.2006.01.020

- Pichi, F., Abboud, E. B., Ghazi, N. G., & Khan, A. O. (2018). Fundus autofluorescence imaging in hereditary retinal diseases. Acta Ophthalmol, 96(5), e549-e561. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13602

- Wilde, C., Awad, M., Giannouladis, K., Lakshmanan, A., Yeung, A. M., Dua, H., & Amoaku, W. M. K. (2020). Natural course of adult-onset vitelliform lesions in eyes with and without comorbid subretinal drusenoid deposits. Int Ophthalmol, 40(6), 1501-1508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-020-01319-2

- Brito-Garcia, N., Del Pino-Sedeno, T., Trujillo-Martin, M. M., Coco, R. M., Rodriguez de la Rua, E., Del Cura-Gonzalez, I., & Serrano-Aguilar, P. (2017). Effectiveness and safety of nutritional supplements in the treatment of hereditary retinal dystrophies: a systematic review. Eye (Lond), 31(2), 273-285. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.286