Haseeb N. Akhtar,*1 Aysha Adil,*1 Ayesha Salejee,*1 Hassan A. Mirza1

*These authors contributed equally.

1University College London, London, UK

Introduction

The mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are a rare group of lysosomal storage disorders, each characterised by deficiency in a specific lysosomal enzyme responsible for glycosaminoglycan (GAG) degradation (1). Pathological accumulation of GAGs occurs in multiple organ systems, including the eye, leading to a broad range of clinical features. Despite MPS being uncommon overall, ocular involvement is relatively frequent within this group of disorders and can significantly compromise vision. This article provides a concise overview of the key ophthalmic manifestations of MPS, highlighting anterior and posterior segment changes, diagnosis and management considerations.

Epidemiology

Collectively, MPS represents an important cohort of lysosomal storage diseases encountered in both ophthalmic and paediatric practice (2). Most MPS types follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, with the notable exception of MPS II (Hunter syndrome), inherited in an X-linked recessive manner (3). The severity and onset of symptoms vary depending on the specific enzyme deficiency, with some individuals remaining asymptomatic until later childhood or adolescence, while others present earlier in the disease course with pronounced ocular and/or systemic manifestations.

Pathophysiology

All MPS subtypes arise from either an absence or deficiency in one of many lysosomal enzymes involved in GAG metabolism (1). The subsequent accumulation of partially degraded GAGs leads to structural and functional disruption in various ocular tissues, including the cornea, sclera, trabecular meshwork, retina, and optic nerve (3). This can manifest as corneal clouding, glaucoma, retinal degeneration, and optic neuropathy, among other ocular issues. Systemically, GAG deposition results in skeletal deformities, organomegaly, and characteristic facies, to varying degrees across the different subtypes.

Clinical Features

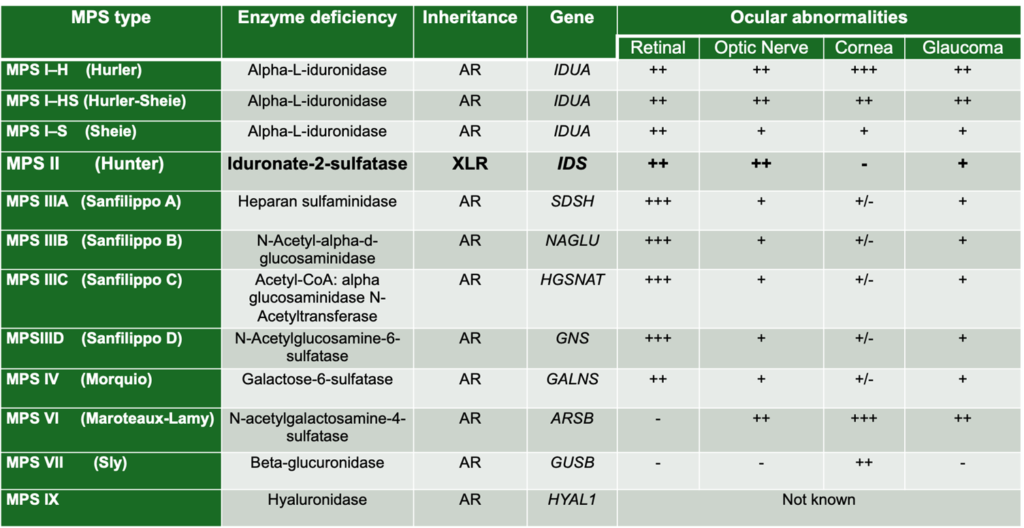

Figure 1 summarises the ophthalmic manifestations in each MPS subtype.

Figure 1: Ophthalmic Manifestations of the Mucopolysaccharidoses – Adapted from Chapter 9.4, Table 9.2, Biswas S, Ashworth JL (2022). Keratopathy in inborn errors of metabolism. In: Black GCM, Ashworth JL, Sergouniotis Pl. (eds) Clinical Ophthalmic Genetics and Genomics 1st Edition.

Anterior Segment Manifestations

Corneal clouding is a hallmark in several subtypes, notably MPS I and MPS VI (4). GAG deposition disrupts the regular spacing of collagen fibrils in the cornea, causing progressive opacification and reducing visual acuity. Intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation and glaucoma may arise from either abnormal trabecular meshwork or altered anterior chamber angles (5). MPS I-H (Hurler), MPS I-HS, and MPS VI are particularly prone to glaucoma.

Posterior Segment Manifestations

Deposits in the retina and optic nerve can produce optic nerve swelling, atrophy and pigmentary retinopathy respectively. Optic neuropathy may be caused by local GAG accumulation or raised intracranial pressure (6). MPS III (Sanfilippo) is notably associated with progressive retinal degeneration, leading to visual decline (7).

Systemic Manifestations

MPS disorders often present with multi-system involvement, including:

- Abnormal Facies: Coarse facial features (including macroglossia and a depressed nasal bridge) are common in MPS I and MPS VI; milder facial features can be seen in MPS II (1,2,3,12).

- Reduced IQ/Developmental Delay: Cognitive impairment reflects the degree of central nervous system GAG storage. MPS I (Hurler) typically results in severe developmental delay, while MPS II (Hunter) and MPS VII (Sly) can have variable cognitive involvement (3). MPS III (Sanfilippo) is characterised by profound, progressive neurodegeneration, whereas MPS IV (Morquio) and MPS VI (Maroteaux-Lamy) generally spare cognitive function (3,13,14).

In the paediatric setting, these systemic clues – combined with early ocular findings – should raise the index of suspicion for MPS.

Diagnosis

Prompt recognition of ocular changes, such as corneal clouding and optic nerve swelling, can expedite diagnosis (8). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) helps detect structural corneal or retinal abnormalities (8). Fundus autofluorescence imaging can reveal characteristic pigmentary or atrophic changes, particularly in the posterior segment (7). Systemic evaluation (e.g. urinary GAG analysis, enzyme assay and genetic testing) is crucial for definitive diagnosis.

Management

Treatment remains largely supportive but has advanced significantly in recent decades:

- Corneal transplantation: severe corneal opacities may be addressed by penetrating keratoplasty or deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty; recurrent GAG deposition in donor tissue can limit long-term graft clarity (9).

- Glaucoma therapy: medical management with multiple topical IOP lowering agents, laser procedures (e.g. laser iridotomy) or surgical interventions (trabeculectomy or tube shunts) may be necessary in order to achieve sustained IOP control (5).

- Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT): this is available for several MPS subtypes (e.g. Hurler-Scheie, Maroteaux-Lamy, Hunter); ERT may stabilise or slow disease progression, including some ocular manifestations (10).

- Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): particularly beneficial in severe MPS I (Hurler); it can improve lifespan and attenuate systemic features, although its efficacy in stopping deterioration in ophthalmic outcomes varies (3).

- Gene therapy: ongoing research is examining gene augmentation strategies in MPS, with early studies suggesting that targeted central nervous system delivery could mitigate neurodegeneration; ocular approaches are still under investigation (11,14,15).

Conclusion

Although mucopolysaccharidoses are rare lysosomal storage disorders, ocular manifestations – ranging from corneal clouding and glaucoma to retinal degeneration – are relatively common within this group. Early recognition of the eye findings can prompt timely referral for systemic investigations, leading to more effective multidisciplinary management. Advances in ERT, HSCT and potential gene therapies do offer hope for improved prognosis, but challenges remain, particularly in preserving long-term visual function. A thorough understanding of the clinical spectrum of this disease entity and future therapeutic options will be essential for all clinicians involved in caring for patients with MPS.

References

1. Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 3421–52.

2. Wraith JE. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a clinical review and guide to management. Arch Dis Child. 1995;72(3):263–7.

3. Ashworth JL, Biswas S, Wraith E, Lloyd IC. The ocular features of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Eye (Lond). 2006;20(5):553–63.

4. O’Leary LA, Jones SA, McKay VH, Ashworth JL. Corneal clouding in mucopolysaccharidosis. Clin Exp Optom. 2011;94(2):146–54.

5. Saadoun D, Waters PJ, Marzouk O, McDonald HR. Ocular complications in mucopolysaccharidoses. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(8):1578–84.

6. Gelb BD, Scott CI, He X, Desnick RJ. Optic nerve involvement in mucopolysaccharidoses. J Med Genet. 1999;36(2):126–30.

7. Fahnehjelm KT, Chen E, Winiarski J, Andersson S, Olsson M. Retinal degeneration in mucopolysaccharidosis III. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82(4):457–62.

8. Beck M, Cole TJ, Joshi C, Morin G. Advances in ophthalmic diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(5):514–26.

9. Chan TK, Ho M, Lam DS, Cheng AC. Long-term results of penetrating keratoplasty in mucopolysaccharidoses. Cornea. 2003;22(6):553–9.

10. Dickson PI, Kimura R, Pivnick EK, Grange DK. Enzyme replacement therapy in lysosomal storage disorders: limitations and new frontiers. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2015;12(1):132–40.

11. Wang RY, Bodamer OA, Watson MS, Wilcox WR. Gene therapy for mucopolysaccharidoses: current status and future prospects. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;102(3):167–75.

12. Valayannopoulos V, Nicely H, Harmatz P, Turbeville S. Mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:5.

13. Andrade F, Aldámiz-Echevarría L, Llarena M, Couce ML. Sanfilippo syndrome: Overall review. Pediatr Int. 2015;57(3):331–8.

14. Herati RS, Knox VW, O’Donnell PA, Wolfe JH, Muenzer J. Central nervous system-directed gene therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis I: Injection of AAV vectors into the cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Ther. 2008;16(9):1451–7.

15. Wraith JE. The clinical presentation of mucopolysaccharidoses. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1999;88(433):3–9.