Elliott H Taylor*, Ben Smith*, Karima Nesnas

*denotes joint first authorship

NHS Frimley Health Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

Background

Ophthalmology is the busiest outpatient specialty (1). Currently there is significant pressure on NHS ophthalmology services, exacerbated by a backlog of over 600,000 patients and workforce shortages (2,3). Efforts to improve the efficiency of ophthalmology services is vital. In our hospital, eye emergencies are initially assessed by emergency department (ED) clinicians, as there is no walk-in eye casualty service. It has been consistently demonstrated that junior doctors have low confidence in the assessment and management of eye emergencies,(4) and it is likely a high proportion of cases presenting to the ED are referred to the emergency eye clinic (EEC). Given the challenges facing ophthalmology services, there is an urgent need to optimise referral pathways, to facilitate effective triage of eye emergencies.

Aims

We aimed to conduct a closed loop audit to assess and improve the quality of referrals from the ED to the EEC, in line with referral information standards set by the Professional Record Standards Body(PRSB) (5).

Methods

This audit was conducted at Frimley Park Hospital, United Kingdom and was registered and approved prospectively by the local quality improvement and audit department. We adhered to the following pre-defined structure: (i) develop contextually adapted referral standards from referral information standards set by PRSB; (ii) audit the quality of referrals from the ED to the ECC in relation to the pre-defined standard, (iii) implement a contextually relevant intervention to improve the quality of referrals; and (iv) re-audit the quality of referrals following intervention implementation.

The clinical referral information standards set by PRSB, are endorsed by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. These standards are designed for referrals from general practitioners to hospital consultants and other health care professionals providing outpatient services. Therefore, the PRSB standards were adapted for relevance to our local setting and a within hospital referral. Due to the nature of the electronic patient health records (EPR) system at Frimley Park Hospital, referrals within the hospital system automatically link to the patient record which contains data such as: patient demographics, referrer details, allergies and adverse reactions, medications, safety alerts, investigation results, past medical and surgical history. We therefore focussed on the clinical content of the referral – primarily covered in the ‘reason for referral’ and ‘examination findings’ sections of the PRSB standards. Through consulting key stakeholders from the ED and EEC, the following information domains were considered essential and were set as the required standard: (i) reason for referral, (ii) clinical urgency, (iii) laterality, (iv) symptoms, (v) duration of symptoms, (vi) visual acuity, (vii) other eye examination findings, (viii) suspected diagnosis, (ix) treatment given. We determined that >90% of referrals should contain these key information domains. As reason for referral and clinical urgency were already a mandatory part of the existing referral form, we focussed on information points 3-9 for the purposes of this audit. The pre-existing electronic referral form had a free text field where information points 3-9 could potentially be added, though we hypothesised that few referrals contained this information.

The primary outcome was the proportion of referrals containing each of the key referral information domains – as per the defined standard. In the pre-intervention audit we collected quantitative data on 100 consecutive referrals over a one-month period. A combined intervention was subsequently developed and implemented, including an updated electronic referral form and an educational poster. In the post-intervention audit we repeated the same data collection process (assessing 100 consecutive referrals over a one-month period) to assess if the quality of referrals had improved following intervention implementation.

Results

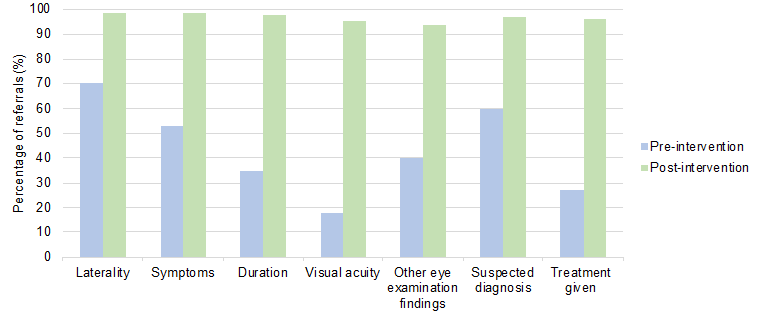

The pre-intervention baseline audit assessed 100 consecutive referrals from April 2023. All key information domains were documented in less than 90% of referrals. Only ‘laterality’ (70%), ‘suspected diagnosis’ (60%), and ‘symptoms’ (53%) were documented in more than half of referrals. The ‘duration of symptoms’ (35%), ‘visual acuity’ (18%), ‘other eye examination findings’ (40%), and ‘treatment given’ (27%) were all documented in less than half of referrals (figure 1).

An updated referral form was designed in collaboration with key stakeholders from the ED and EEC. The new electronic referral form included sub-headings for each of the key referral information domains. In addition, an educational poster was designed and placed in the eye assessment room within the emergency department – informing clinicians of the updated referral form and the key clinical information required.

The post-intervention audit assessed 100 consecutive referrals between November and December 2023. There was a significant improvement, with all key information domains documented in over 90% of referrals: laterality (99%), symptoms (99%), duration of symptoms (98%), visual acuity (95%), other eye examination findings (94%), suspected diagnosis (97%), treatment given (96%) (figure 1).

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this closed loop audit we recommend: (i) continued use of the updated referral form, (ii) ongoing education relating to both the importance of thorough referral documentation and the assessment and management of eye emergencies, (iii) regular re-audit, (iv) expansion to EEC referral systems in other hospital trusts – particularly those using the ‘Epic’ EPR system (6).

Conclusion

This closed loop audit assessed the quality of referrals from ED to the EEC based on a referral standard adapted from the referral information standard (PRSB). Baseline audit showed that the quality of referrals was low – only three of the seven key information domains were documented in more than 50% of referrals. We then implemented an updated electronic referral form and an educational poster. The post-intervention audit showed that all key information domains were documented in more than 90% of referrals – meeting the pre-defined referral standard. The improved quality of referrals may facilitate more effective EEC triage. This may help relieve some of the existing pressure on local ophthalmology services, and we recommend continued use of the updated referral system.

References

1. NHS Digital [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 24]. Hospital Outpatient Activity 2022-23. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-outpatient-activity/2022-23

2. RCOphth workforce census reveals serious NHS ophthalmology workforce shortages and growing role of independent sector providers [Internet]. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. [cited 2023 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/news-views/rcophth-census-2022-report/

3. Statistics » Consultant-led Referral to Treatment Waiting Times Data 2022-23 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/rtt-waiting-times/rtt-data-2022-23/#Mar23

4. Sim PY, La CJ, Than J, Ho J. National survey of the management of eye emergencies in the accident and emergency department by foundation doctors: has anything changed over the past 15 years? Eye. 2020 Jun;34(6):1094–9.

5. Clinical referral information v1.1 – PRSB [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 26]. Available from: https://theprsb.org/standards/clinicalreferralinformation-2/

6. Epic | …With the patient at the heart [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 26]. Available from: https://www.epic.com/