Shivam Goyal

Background

Glaucoma-filtering procedures (e.g., trabeculectomy) is a standard surgical procedure commonly done when maximally tolerated medical therapy or laser trabeculoplasty fails to adequately control intraocular pressure (IOP). The filtering procedure creates a fistula between the anterior chamber and the subconjunctival space, covered with thin sclera and conjunctiva that allows excess aqueous humour to be absorbed into the systemic circulation. Thus, the presence of a filtering bleb poses an enduring risk of a bleb related infection (BRI) over the patient’s lifetime (1).

To improve the success of these procedures, it has now become routine to use intraoperative antifibrotic agents (e.g., mitomycin and fluorouracil) as an adjunct to standard trabeculectomy (2). Although these agents have improved the chances of long-term IOP control they have further predisposed to an increased incidence of postoperative complications including late-onset filtering bleb-related infections (1).

Infection can be localized to the filtering bleb (blebitis) with varying degrees of anterior segment inflammation or can rapidly spiral into a full-blown bleb-related endophthalmitis (BRE) characterised by hypopyon and cells in the vitreous. BRE is a serious complication and can result in permanent visual loss.

Blebitis and BRE may thus represent a continuum of infection, and this distinction is crucial due to difference in initial management, treatment, and prognosis. We describe a case of BRE which developed several years following the glaucoma filtration surgery and while responding to treatment developed retinal detachment (RD) further compromising the outcome. We also aim to describe risk factors associated with BRI and discuss current concepts of management.

Case

A 76-year-old patient was referred to our casualty clinic with 2 days history of red, painful right eye. She also complained of sensitivity to light (photophobia) and loss of vision. Patient had upper respiratory tract infection symptoms a week before but denied any red eye apart from excessive mucoid discharges in both eyes. Our patient was otherwise fit and well with statins as her only regular medication.

The patient had complicated and an extensive past ocular history with bilateral retinal detachment repair surgeries in the past; 18 years ago, in the right eye and 16 years ago in the left eye (Bilateral Vitrectomy + Cryotherapy + Gas). She was a known case of advanced open angle glaucoma in both eyes. She had right cataract surgery with an intraocular lens implant 9 years ago followed by a right trabeculectomy with Mitomycin C (MMC) 2 years later. The left eye underwent a trabeculectomy with MMC 8 years ago with a cataract procedure 1 year later. Patient’s IOPs were well controlled with IOP of under 10 without any need for anti-glaucoma drops.

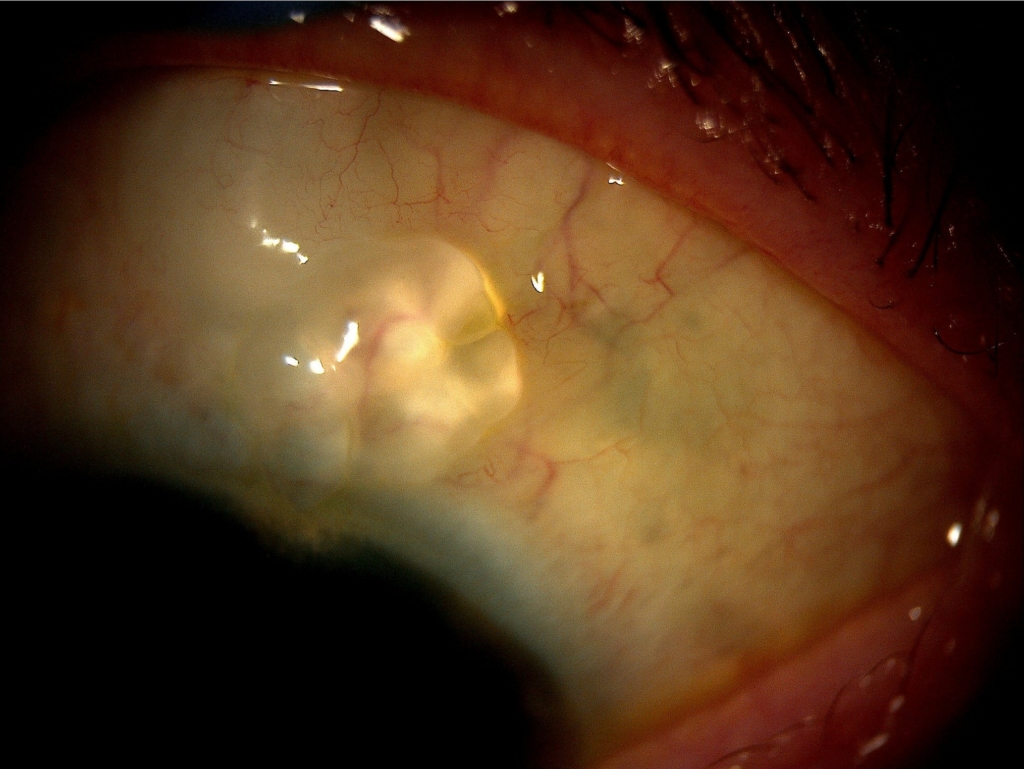

On examination, right BCVA was Perception of Light and left BCVA was 6/12. Right IOP was 33. Right eye was very injected with white opaque cystic bleb (Figure 1). There was corneal oedema, extensive uveitis with fibrinous reaction and 1mm hypopyon but anterior chamber was deep with no bleb leakage. Due to dense anterior chamber reaction, the fundus view was not possible in right eye. B scan of right eye showed flat retina with some degree of vitreous debris. Left eye examination was unremarkable.

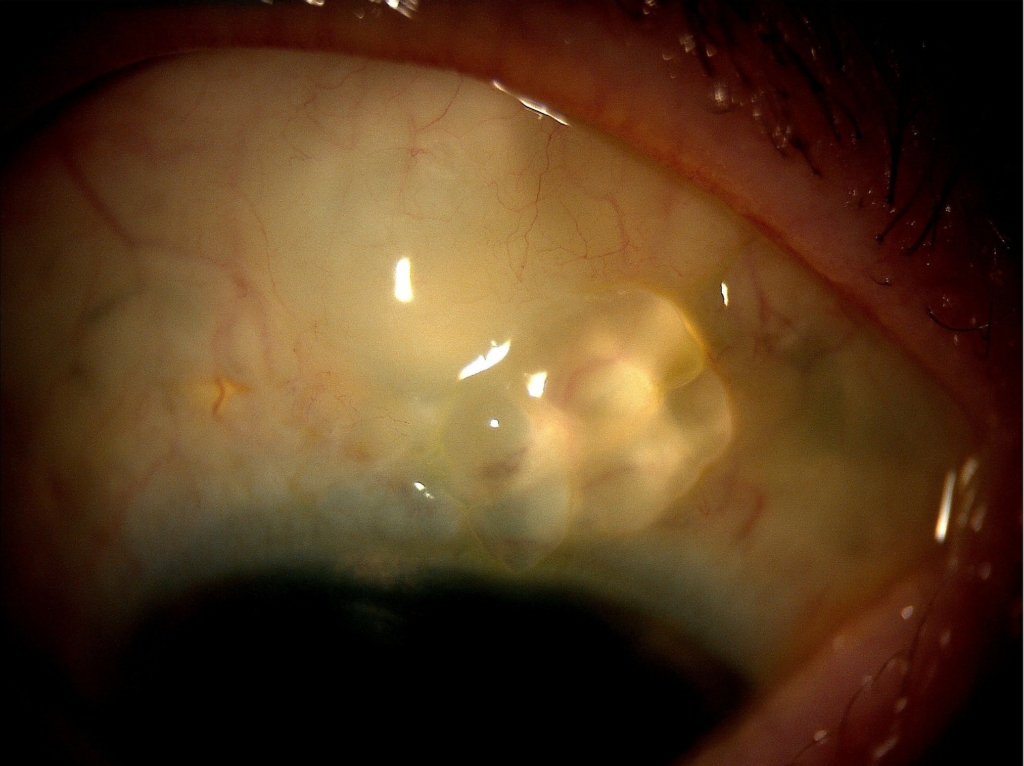

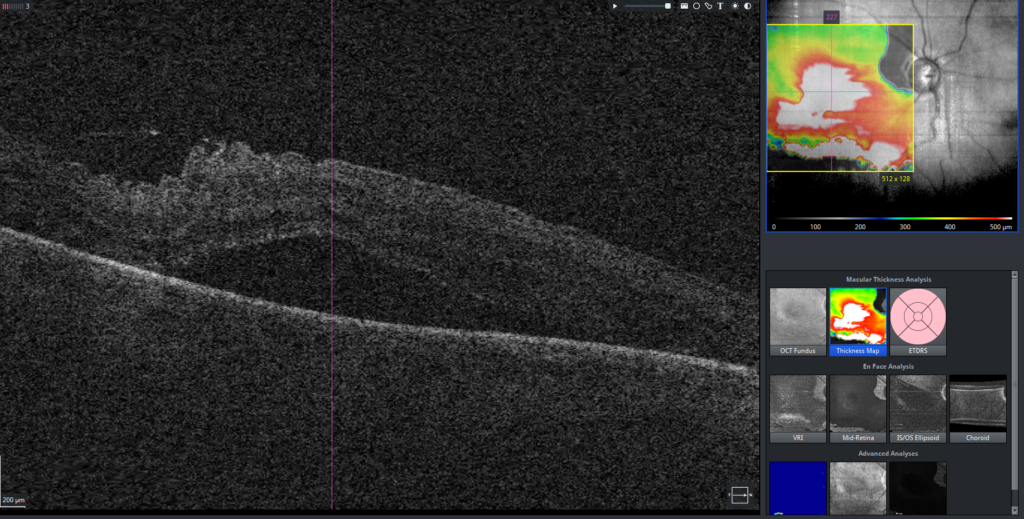

A diagnosis of Right BRE was made due to dense anterior chamber inflammation / hypopyon and vitreous involvement. On the same day and patient had an anterior chamber tap (AC tap) vitreous biopsy and intravitreal Ceftazidime and Vancomycin. She was also treated with topical fortified antibiotics and oral ciprofloxacin. AC tap and Vitreous biopsy didn’t grow any organisms. Endophthalmitis improved slowly with improvement in acuity to 6/60 and the eye became white with a cystic looking bleb (Figure 2). On 5 weeks follow-up, she was noted to have inferior macula off RD (Figure 3). Patient had retinal detachment repair on the next day. At the last follow up though the retina appeared anatomically flat, vision was poor at hand movement / count fingers.

Discussion

The incidence of blebitis and endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy is higher than most other intraocular procedures (3). It has been estimated that the prevalence of acute postoperative endophthalmitis after any type of intraocular surgery is 0.093% (4), whereas the reported incidence of late postoperative bleb-related infections after trabeculectomy ranges from 0.4% to 6.9% in several studies over the past decade (3). After trabeculectomy with mitomycin, it is estimated that blebitis occurs with an incidence of 5.7% per year, whereas the incidence of endophthalmitis ranges between 0.8% to 1.3% per year (1,5).

Several risk factors have been associated with an intraocular infection after trabeculectomy. The inferior or nasally located bleb is one of the earliest recognised factors associated with BRI via exposure of the bleb to the bacteria rich lacrimal lake (6). It has been suggested that the presence of a high bleb and blepharitis increases the risk of bleb related infection. Among the most important risk factors for bleb infection is the presence of bleb leakage (7). The pathogens from the tear film have direct access to the anterior chamber via the leaking bleb thus bypassing the conjunctiva and the sclera. It is known that use of anti-fibrotic agents leads to a greater rate of late onset bleb leakage than trabeculectomy without them. Histologically blebs after trabeculectomy with MMC have irregularities in the conjunctival epithelium, breaks in the basement membrane, conjunctival and sub-conjunctival hypo-cellularity which can all predispose to bleb leaks. A recent study has shown that MMC use is strongly associated with BRI (8).

The presence of MMC augmented trabeculectomy made our patient susceptible to BRE. Though the bleb was not actively leaking in the acute phase, the thin cystic and avascular nature of the bleb (figure 2) which was visible once the infection was controlled predisposed the eye to pathogen entry. It has been postulated that the combination of defects in the bleb’s barrier function with altered conjunctival innate immune defences may play a role in the observed increased susceptibility to infection of antimetabolite-augmented trabeculectomy blebs (9).

Other risk factors associated with BRI are intermittent or chronic use of topical antibiotics beyond the immediate postoperative period (8), the use of systemic corticosteroids, juvenile glaucoma, silk conjunctival sutures, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, releasable sutures, pale-coloured blebs, contact lens wear, younger age at the time of surgery and black race.

In early bleb-associated endophthalmitis, the most common bacteria include the coagulase-negative Staphylococcus sp. and Propionibacterium acnes, which usually have a favourable prognosis for good visual acuity once the infection Resolves (10). In contrast, late-onset bleb-associated endophthalmitis is usually caused by Streptococcus sp. and gram-negative bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae, which have a poorer prognosis for vision (11).

BRI is an urgent condition that needs instant intensive treatment. It is essential to detect the disease early, distinguish the disease stage and identify the organism responsible. The treatment should comprise a combined therapy of fortified topical, subconjunctival, or intra-ocular injection of antibiotics, and systemic antibiotic therapy depending on the severity of infection. Vitrectomy is mostly recommended when vitreous involvement is apparent or severe. Considerable controversy exists regarding the use of concomitant topical or intravitreal corticosteroids in the management of late-onset bleb related infections. It is believed that these agents modify the inflammatory response and the resultant damage to ocular structures; however, no research has yet supported their use in this setting (12).

A severe complication of endophthalmitis is subsequent development of RD which has been reported in 25% of cases of endophthalmitis. There does not exist an evidence-based consensus on the risk factors that contribute to the development of RD after endophthalmitis. A few studies have suggested that the virulence of organisms, posterior capsular rupture after cataract surgery, vitreous prolapse and diabetes are risk factors for the development of RD after endophthalmitis. Though seldom reported, RD may occur as a result of membranous scar tissue formation after the inflammation has settled. In a study conducted by Wang et al the incidence of RD after endophthalmitis was 14.8% (n=16/108) however none of the endophthalmitis was bleb related (13). However, another potential contributor to the development of RD is the invasive nature of intraocular procedures such as intravitreal antibiotics and pars plana vitrectomy used for treating endophthalmitis (14). Our patient did not have vitrectomy but had vitreous biopsy and intravitreal antibiotics and it has been suggested that a “jet stream” effect induced by intravitreal injection could create a retinal tear, especially in patients who have undergone vitrectomy like our patient (14). The “jet stream” effect happens when high velocity of fluid stream from the needle damages fragile retina with no vitreous cushion (14). The other possibility in our patient is that the severity of intraocular inflammation at the time of diagnosis of endophthalmitis contributed to the development of RD.

Conclusion

Considering the devastating consequences of bleb associated endophthalmitis, it is critically important to educate patients about the possible lifelong risks, symptoms, and signs of bleb-related infections which include Redness, Sensitivity to light, Visual acuity decline of sudden onset and Pain in the eye. The pneumonic ‘RSVP’ may be helpful.

Patients must seek immediate ophthalmic attention upon experiencing symptoms and general physicians should be educated not to misdiagnose blebitis as viral conjunctivitis as it can happen many years following surgery and discharge the patient without recognising the risk of endophthalmitis. In addition, RD after endophthalmitis is often associated with poor anatomic and visual outcomes and patients should be counselled regarding this.

References

1. DeBry P. Incidence of Late-Onset Bleb-Related Complications Following Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2002;120(3):297.

2. Robin A. A Long-term Dose-Response Study of Mitomycin in Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1997;115(8):969.

3. Poulsen E, Allingham R. Characteristics and Risk Factors of Infections After Glaucoma Filtering Surgery. Journal of Glaucoma. 2000;9(6):438-443.

4. Aaberg T, Flynn H, Schiffman J, Newton J. Nosocomial acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis survey. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(6):1004-1010.

5. Parrish R, Minckler D. “Late Endophthalmitis”—Filtering Surgery Time Bomb?. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(8):1167-1168.

6. Caronia R. Trabeculectomy at the Inferior Limbus. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1996;114(4):387.

7. Soltau J. Risk Factors for Glaucoma Filtering Bleb Infections. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2000;118(3):338.

8. Jampel H. Risk Factors for Late-Onset Infection Following Glaucoma Filtration Surgery. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2001;119(7):1001.

9. Lehmann O. Risk factors for development of post-trabeculectomy endophthalmitis. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;84(12):1349-1353.

10. Beck A, Grossniklaus H, Hubbard B, Saperstein D, Haupert C, Margo C. Pathologic findings in late endophthalmitis after glaucoma filtering surgery. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(11):2111-2114.

11. Song A, Scott I, Flynn M, Budenz D. Delayed-onset bleb-associated endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(5):985-991.

12. Reynolds A, Skuta G, Monlux R, Johnson J. Management of Blebitis by Members of the American Glaucoma Society: A Survey. Journal of Glaucoma. 2001;10(4):340-347.

13. Wang T, Moinuddin O, Abuzaitoun R, Hwang M, Besirli C, Wubben T et al. Retinal Detachment After Endophthalmitis: Risk Factors and Outcomes. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2021;Volume 15:1529-1537.

14. Nelsen P, Marcus D, Bovino J. Retinal Detachment Following Endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(8):1112-1117.