Mark McKeague

Case Report

A 38 year old white male patient presented to his community optometrist complaining of a four day history of painless blurred vision in the right eye that he described as “like looking through a glazed-bathroom window”. He had noted one similar episode two weeks previously that self-resolved within 2 hours. The patient was otherwise well and symptom free; he denied any pain or antecedent trauma and there was no history of recent surgery, travel or illness.

He had no past ocular history and premorbid visual acuity was 6/6 bilaterally. There was no past medical history, and no family history of note.

He was not taking any regular medication and had no known allergies to medications.

The patient was an ex-smoker with a less than five pack-year history and did not consume alcohol or use recreational drugs.

He was working at a local bus company and lived at home with his family. Of note his main hobby was marathon running, training on 6 days per week with intense sessions being conducted at the time of the event in anticipation of upcoming marathons. He denied training in hypoxic conditions such as altitude tents; however during further discussion, the patient agreed that he was likely not maintaining adequate hydration whilst training.

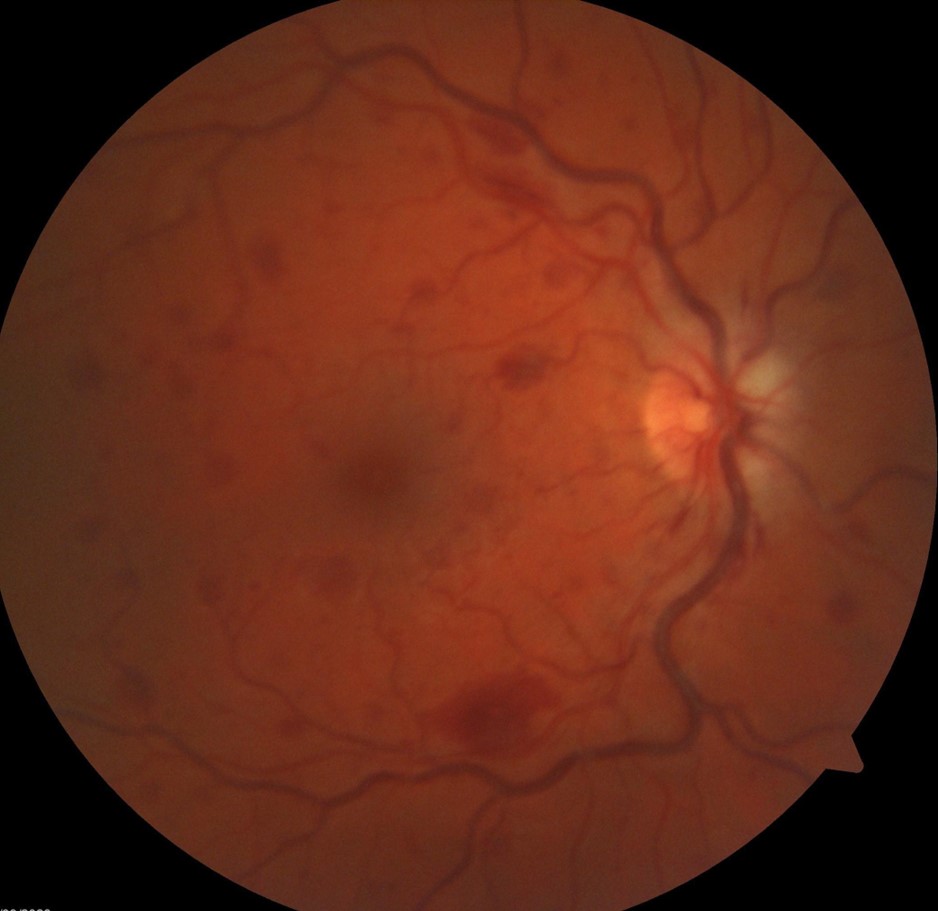

The patient was normotensive and all physical observations were within normal limits. On examination there were no focal neurological deficits, and best corrected visual acuity was 6/18 in his right eye and 6/6 in the left. Pupillary reactions were normal with no relative afferent pupillary defect. Intra ocular pressure was within normal limits bilaterally. Fundoscopy revealed multiple haemorrhages throughout the retina and a naso-temporal cotton wool spot at the disc as well as mild nasal disc oedema. An OCT scan showed minimal macular oedema and the following image was taken at time of presentation:

Figure 1. Fundus camera image taken at time of presentation – Right eye.

Following discussion with the on-call ophthalmology services, he was referred to the local macular clinic where he was diagnosed with a central retinal vein occlusion and investigated for potential causes. All blood tests were unremarkable, including fasting lipids, clotting, haematocrit, biochemistry, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and autoimmune screen. Given the patient’s extreme physical training regimen and entirely normal investigations it was decided the likely aetiology of his vein occlusion was dehydration.

It was decided to manage the patient conservatively and give lifestyle advice regarding adequate hydration whilst marathon training. He was not started on any anticoagulation or treated with anti-VEGF medications. On review 8 weeks later, his vision had returned to 6/6 bilaterally and he had not encountered any further visual disturbances. He continues to pursue marathon running as a hobby and has successfully competed in 2 marathons since symptom onset. However, he reports that he is now very diligent at ensuring adequate hydration during training sessions.

Discussion

We present a case above of a spontaneous central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) in an otherwise well 38-year-old marathon runner. A small number of similar cases have been described in the literature, with dehydration causing CRVO in young athletes (1,2). CRVO most commonly occurs in patients over the age of 50 who have identifiable risk factors for vascular disease (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia etc.) The pathophysiology of CRVO, as with any thrombotic disease, is related to either venous stasis, endothelial damage or hypercoagulability.

It has been postulated that in extreme dehydration a transient rise in haematocrit will create a hyperviscous state in which thrombosis can occur. The central retinal vein is particularly susceptible to this, especially in the region of the lamina cribrosa (3).The image of our patient shown above displays many of the classic examination findings of CRVO, which can be described as having a “blood and thunder” appearance.

Prognosis for patients with CRVO is generally better the younger the patient is, and in those without significant macular oedema or visual loss at presentation. In patients without significant ischaemia the prognosis is also much better and 50% of those cases will make a full or near-full recovery (4).

Several of the previously published case reports of CRVO secondary to dehydration have been managed with VEGF inhibitors, however our patient has made an excellent recovery with purely conservative management and lifestyle changes (1).

This case should highlight the importance of taking a thorough social history when assessing young patients presenting with CRVO, ensuring to enquire about exercise habits. It is an unusual case with only a handful of similar cases noted in the literature. Our patient has made a full recovery with purely conservative management.

References

1. Moisseiev E, Sagiv O, Lazar M. Intense exercise causing central retinal vein occlusion in a young patient: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr 5;5(1):116-20. doi: 10.1159/000360904. PMID: 24847256; PMCID: PMC4025055.

2. Francis PJ, Stanford MR, Graham EM. Dehydration is a risk factor for central retinal vein occlusion in young patients. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003 Aug;81(4):415-6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00095.x. PMID: 12859276.

3. Williamson TH. A “throttle” mechanism in the central retinal vein in the region of the lamina cribrosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 Sep;91(9):1190-3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.102798. Epub 2006 Sep 27. PMID: 17005545; PMCID: PMC1954902.

4. Kyle Blair; Craig N. Czyz. (2023) Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. In StatPearls. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525985/ [Accessed 27.01.2023]