Rana Khalil1

1Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin, Ireland

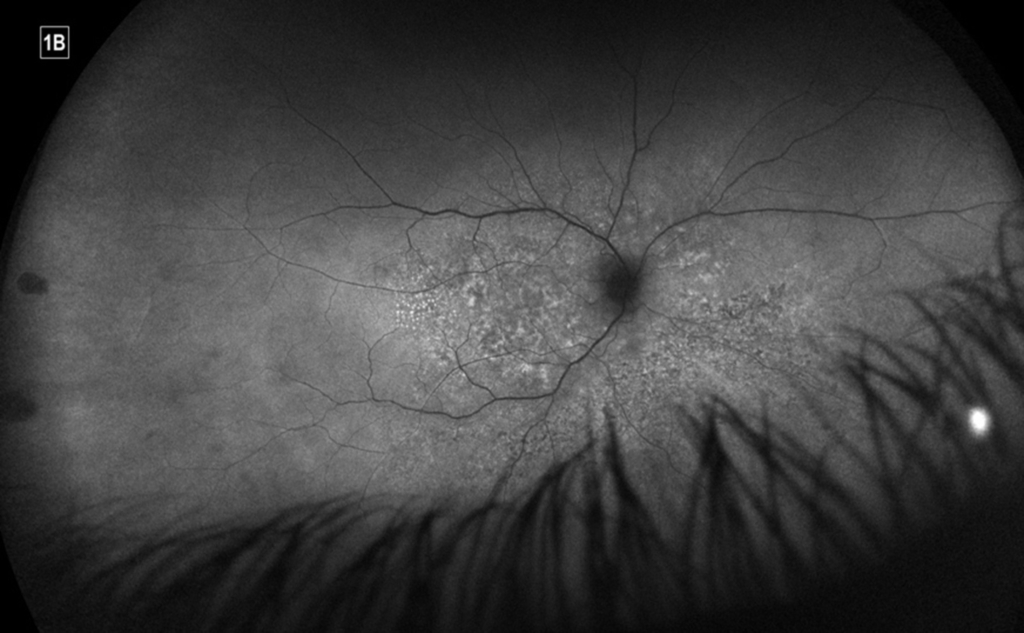

A 47-year-old man presented with a one-week history of reduced right visual acuity, epiphora, and painful eye movements. This was on a background of two self-resolving episodes of left hand paraesthesias in the four weeks prior. He did not have any significant past medical history and denied trauma. At presentation, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of the right eye was limited to hand movements. Examination revealed a clear cornea with slight endothelial haze, occasional anterior chamber, and a quiet vitreous. The optic nerve was diffusely swollen with surrounding splinter haemorrhages, areas of patchy chorio-retinal pallor extending inferonasally and arterio-venous nicking (Figure 1A and 1B).

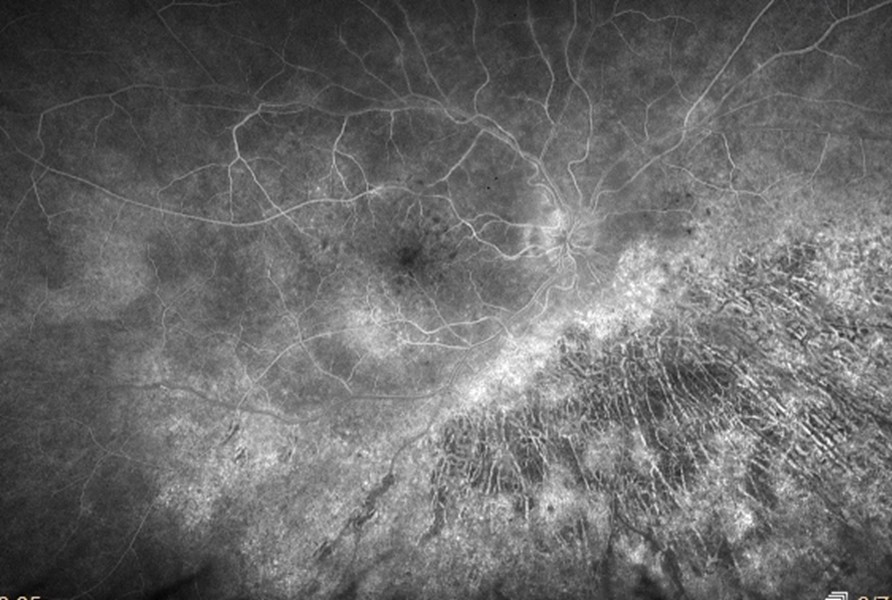

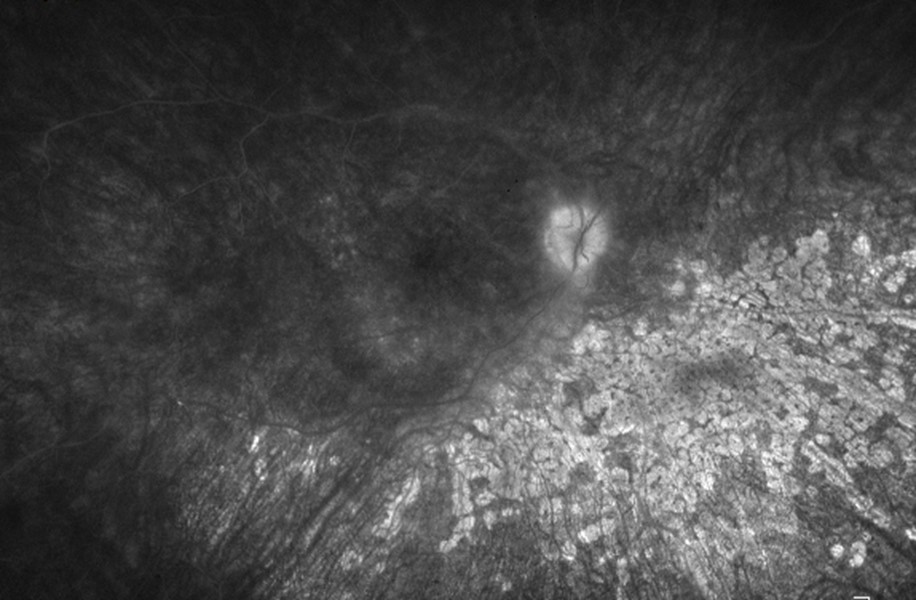

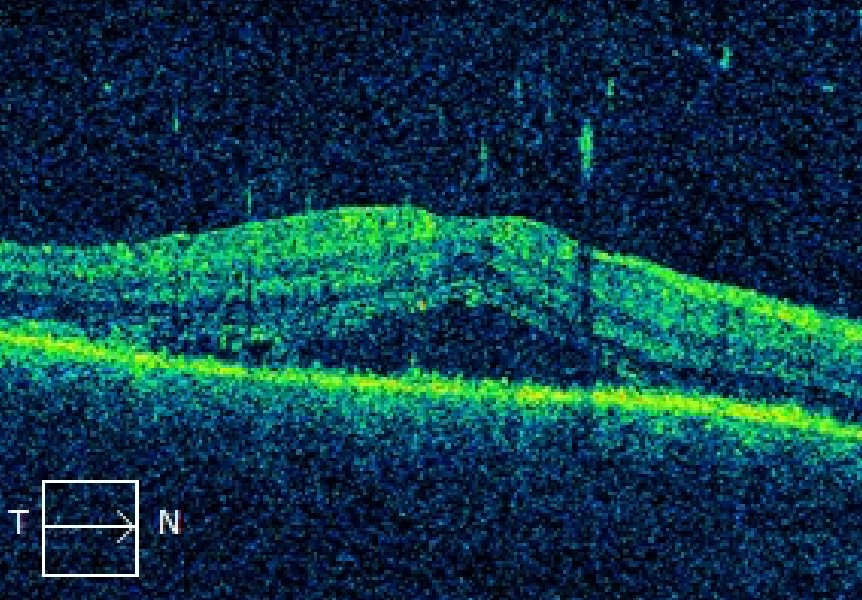

A dense relative afferent pupillary defect was noted. Intraocular pressure was 10mmHg. Examination of the left eye was normal. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) suggested the presence of chorioretinitis, corresponding to the examination findings (Figure 2). Additionally, there was evidence of subretinal fluid on optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Figure 3). The working diagnosis was right panuveitis with mainly posterior involvement. Initial investigations including serum inflammatory markers, autoimmune screen, hepatitis, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, HIV and chest x-ray returned negative.

The patient was consequently commenced on topical prednisolone acetate 1.0% drops whilst awaiting contrast MRI brain and orbits, and syphilis/bartonella/brucella serology results. Steroid therapy was largely non-beneficial, except in resolving the posterior pole splinter haemorrhages. MRI showed abnormal T2 hyperintensity within the intraconal fat adjacent to the right optic nerve sheath, predominantly in the lateral and inferior aspects of the orbit. Syphilis serology returned as positive several days later, and given the ocular and peripheral neuropathy findings, a referral to infectious diseases was made and a lumbar puncture performed. This confirmed the diagnosis of neurosyphilis (cerebrospinal fluid analysis returned elevated protein, lymphocytosis, and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory result of 1:16). The patient was commenced on a two-week course of intravenous benzylpenicillin, and tapering topical steroids were continued for a total of three months. There was a marked improvement of symptoms, with resolution of both optic nerve head oedema and chorioretinal lesions. Repeat OCT showed improvement of macular oedema. At three months’ follow-up, BCVA of the right eye was 6/20 with IOP 20mmHg. Serial lumbar punctures were continued under the care of the infectious diseases team to monitor disease progression.

Despite a surge in sexual health promotion and prevention over the last two decades, Ireland is facing a growing epidemic of sexually transmitted illnesses (STI) with recent reported cases reaching an all-time high (1). Syphilis is an STI caused by the spirochete treponema pallidum that is associated with HIV co-infection in up to 70% of individuals (2), especially in men who have sex with men (MSM) (3). The presence of HIV may result in a faster progression to neurosyphilis (4).

Known as the ‘Great Imitator’, ocular syphilis often mimics a variety of ocular inflammatory conditions, and as such can pose a challenge to diagnosis. It is classically associated with secondary syphilis, however may present in all stages of disease (5). Presentations include scleritis, interstitial keratitis, iritis, chorioretinitis, papillitis, retinal vasculitis, exudative retinal detachment and optic and cranial neuropathies (6). Non-treponemal tests (VDRL, RPR) are used for screening and to monitor response to treatment, while treponemal tests (FTA-ABS, TPPA) are used for confirmation of diagnosis and remain positive for life (7).

It is recommended that a lumbar puncture be performed in all cases of serologically-confirmed ocular syphilis, even in the absence of neurologic abnormalities (8). Standard neurosyphilis treatment needs to be instituted regardless of the CSF result, as a non-reactive CSF-VDRL test does not exclude a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. In the case of positive CSF results, serial lumbar punctures are recommended to assess treatment response (8). Treatment involves intravenous benzylpenicillin for 14 days. In cases of penicillin allergy, alternatives include intravenous ceftriaxone. Concurrent topical or oral steroids are used to control inflammation and prevent a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (8). There is no microbiological test of cure; treatment success is measured by improvement in clinical and CSF findings.

This case was atypical due to unilateral symptoms, absence of HIV co-infection, and poor visual outcomes despite presentation within 4 weeks of ocular symptoms. As STIs pose a significant public health concern, and with their incidence on the rise, syphilis is an important differential in cases of atypical or treatment-resistant uveitis. To reduce ocular morbidity, ophthalmologists need to be vigilant of the range of presentations of this disease and be reminded that even mild disease can mask potentially sight and life-threatening illness. Education on safe sex practices for patients and their partners, the removal of stigma surrounding STIs as well as improving syphilis surveillance among gay, bisexual and other MSM is therefore necessary.

References

1. Health Protection Surveillance Centre. Syphilis 2021. Available from: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/sexuallytransmittedinfections/syphilis/. [Accessed 19 Dec 2022]

2. Mustapha M, Abdollah Z, Ahem A, Mohd Isa H, Bastion MC, Din NM. Ocular syphilis: resurgence of an old disease in modern Malaysian society. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(9):1573-6.

3. Tsuboi M, Evans J, Davies EP, Rowley J, Korenromp EL, Clayton T, et al. Prevalence of syphilis among men who have sex with men: a global systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000-20. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(8):e1110-e8.

4. Røttingen JA, Cameron DW, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiologic interactions between classic sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: how much really is known? Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(10):579-97.

5. Zhang T, Zhu Y, Xu G. Clinical Features and Treatments of Syphilitic Uveitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6594849.

6. Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis Ocular Manifestations. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing: In: StatPearls [Internet]; [Updated 2022 Aug 22]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558957/.7. Majumder PD, Sudharshan S, Biswas J. Laboratory support in the diagnosis of uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(6):269-76.

8. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(Rr-03):1-137.