Merina Kurian1, Emma Brattle2, Christian Hariman3, Kam Balaggan4

1 Junior doctor, previous Clinical Teaching Fellow at Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust

2 Clinical Teaching Physician Associate, Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust

3 Consultant Physician, Diabetes & Endocrinology, Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust

4 Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon, Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust

As clinical teaching fellows, we have had the privilege to teach medical students between August 2020 to August 2021. In a usual year, this would involve exclusively face-to-face teaching for both lectures and clinical examination sessions. However, following the announcement of the second lockdown in October 2020 we had to adapt our programme. To reduce the number of students on site, one day a week became a ‘virtual learning day’, involving both small and large group tutorials.

Following being tasked with the responsibility of teaching ophthalmology to the fourth-year medical students, an important question loomed: how can we ensure that teaching via a virtual learning platform is both engaging and beneficial? This was further compounded by the fact that ophthalmology is a sub-speciality in which most medical students have limited teaching in the UK (1-3).

Following our experiences, we have outlined the key strategies which enabled us to teach effectively during the pandemic.

1) Virtual teaching platforms

After reviewing the student curriculum, learning requirements and discussing with an ophthalmology consultant, four virtual lectures, each one hour long, were created. They were attended by approximately 20 students every half-term.

The first lecture was titled ‘An introduction to ophthalmology’. This included the basic anatomy of the eye, eyelids, orbit, how to interpret a Snellen chart and the key notions linked to ophthalmoscopy. The slides were visually engaging, using images rather than purely text-heavy explanations to maintain student engagement during this introductory lecture.

The last three lectures focused on important pathologies of the anterior chamber and eyelids, emergency pathologies of the eye and chronic eye conditions. Each one of these lectures were focused on a fictitious case study. The students were given the case and asked to consider what the most likely diagnosis was at the beginning of the lecture from a set of options. The possible pathologies were discussed during the lecture. The answer was revealed at the end of the lecture. The lectures included digital images of the anterior of the eye, fundus photographs and optical coherence tomography (OCT) image, which gave ample opportunity to explain each of these imaging modalities in greater detail.

By focusing on case-based scenarios, students were given the opportunity to consolidate knowledge. The students were engaged and attentive despite the possible animosity towards teaching via virtual learning platform. We received very positive feedback from themedical students following their online teaching experience.

Top Tip: Use images instead of text to maintain student engagement. Concentrate on case based discussions to allow students to consolidate their learning in an interactive way (4).

2) Clinical skills teaching

The creation of an online fundoscopy tutorial, including a step-by-step guide, allowed the students to learn the skill in their own time. This involved explaining the different parts of an ophthalmoscope and then clarifying the instructions to perform the technique. The students were then invited to practice using ophthalmoscopes available from the undergraduate office. As well as this, small group practice sessions were organised and supervised by clinical teaching fellows which meant that the students could gain experienceand feedback on how to improve.

Top Tip: Pre-recorded lectures can be created for clinical skills. Students can watch these in their own time and at their own pace. Following this, organise a small group session where they can be supervised practicing the skill (5).

3) Ophthalmoscopy workshops

As the lockdown rules eased by mid-March 2021, we were able to provide larger group teaching sessions with social distancing and personal protective equipment cover. The ophthalmology workshops were 2 hours long. This comprised of an hour session of multiple mini-stations and an hour of role plays with case-based discussions.

Multiple mini-stations

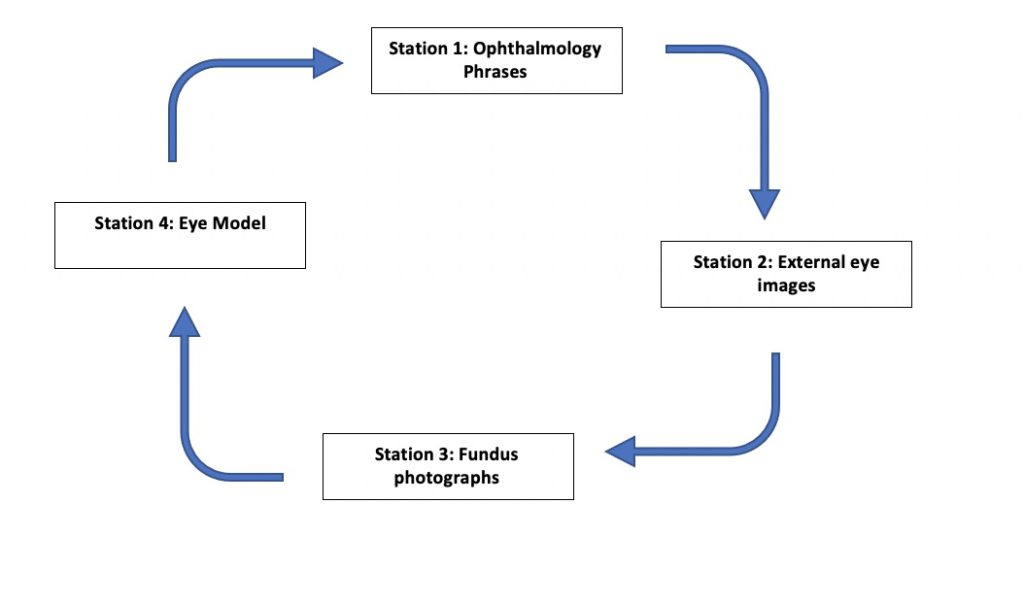

We created 4 team-based exercises for the students to rotate between, lasting 10 minutes per station. This followed the model of multiple mini-stations which are often used as an interview format for healthcare professionals (6,7). The stations were designed to test the knowledge and skills of the students in a friendly but competitive manner (Figure 1). Answers were provided by the teaching fellows for each of the questions at the end of thesession. At the end of the session the highest scoring team won a small prize. The questions and answers were later sent to the students via email to help consolidate their learning.

Station 1: Ophthalmology terminology

The students were given ten medical terms used in ophthalmology and asked to define their meaning. Examples of the words included myopia (short-sightedness) and strabismus (squint).

Station 2: Pathologies of the external eye and anterior segment

The students were shown six images and had the task to describe the likely underlying pathology of each. These images included a patient with bruising around both eyes (base of skull fracture) and a picture of a child with no red eye reflex in the right eye (retinoblastoma).

Station 3: Fundus photographs

The students were shown 5 fundus photographs, then asked to describe the key findings and state the likely underlying pathology. The photographs included findings suggestive of retinal vein occlusion and central retinal artery occlusion.

Station 4: Eye Model

The students were given a fictitious vignette of a young patient presenting to A&E with signs and symptoms of meningitis. They were asked to perform fundoscopy on an eye model which showed papilloedema and then asked how to manage this patient.

Role play and case- based discussions

The students were asked to take part in 2 role play scenarios and 2 case-based discussions.

Case 1: The students took a history from a patient presenting with blurry vision and reduced ability to differentiate colours. Following this, the group of students had a case- based discussion led by the clinical teaching fellow regarding the most likely diagnosis. In this case, the patient had optic neuritis. We discussed the possible underlying diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and its management.

Case 2: The students were asked to take a history of a patient presenting with worsening vision and then test the visual acuity of the patient using a Snellen chart. Through discussion and reviewing fundus images, the patient was concluded as having cytomegalovirus retinitis which is associated with HIV.

Following the workshop, students were given the option of providing feedback of which 10 students participated. 90% of the students found the session to be ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’.

Top Tip: Speciality teaching can be made more interesting by incorporating team and time- based activities with friendly competition. A workshop involving fundoscopy and history- taking can make learning engaging.

4) Speciality placement

Alongside teaching, students were allocated a one-week placement in ophthalmology. During this placement, students were invited to attend a range of clinics and theatre sessions to further enhance and consolidate their learning. Overall, the students gave positive feedback for their ophthalmology placement.

Conclusion

As clinical placements are often the first time that students become properly acquainted with ophthalmology, face-to-face teaching has always been the default method to enable engagement and spark interest.

Teaching ophthalmology during the pandemic and utilising virtual platforms presented new challenges. However as illustrated, there are many strategies which can be used to ensure student safety, engagement as well as satisfaction for both students and staff. As outlined, case-based discussions, role play scenarios, workshops, clinical skill sessions and the development of electronic resources can all be used to enhance student learning.

Even within the confines and limitations enforced by the pandemic, a high standard of teaching has been maintained throughout and excellent student feedback has been received. This will hopefully provide clinicians and healthcare students with the confidence to teach despite the new challenges they may face in the future.

References

1.Baylis O, Murray PI, Dayan M. Undergraduate ophthalmology education – A survey of UK medical schools. Med Teach. 2011;33(6):468–71.

2.Welch S, Eckstein M. Ophthalmology teaching in medical schools: A survey in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2011 May 1 [cited 2021 May 30];95(5):748–9. Available from: https://bjo.bmj.com/

3.Byrd JM, Longmire MR, Syme NP, Murray-Krezan C, Rose L. A pilot study on providing ophthalmic training to medical students while initiating a sustainable eye care effort for the underserved. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):304–9.

4.Bowers EMR, Perzia B, Enzor R, Clinger O, Yadav S, Commiskey PW, et al. A Required Ophthalmology Rotation: Providing Medical Students with a Foundation in Eye- Related Diagnoses and Management. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17(111000).

5.Petrarca CA, Warner J, Simpson A, Petrarca R, Douiri A, Byrne D, et al. Evaluation of eLearning for the teaching of undergraduate ophthalmology at medical school: a randomised controlled crossover study. Eye [Internet]. 2018;32(9):1498–503. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0096-1

6.Eva KW, Macala C, Fleming B. Twelve tips for constructing a multiple mini-interview. Med Teach [Internet]. 2019;41(5):510–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1429586

7.Pau A, Jeevaratnam K, Chen YS, Fall AA, Khoo C, Nadarajah VD. The Multiple Mini- Interview (MMI) for student selection in health professions training-A systematic review. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):1027–41.