Brendan Leng Yong ji

Introduction

Sympathetic ophthalmia (SO) is a bilateral granulomatous uveitis following penetrating ocular trauma or surgery (1). It is a rare but important cause of irreversible visual loss in trauma. Early identification and intervention is therefore vital in mitigating the long term effects of this potentially sight threatening disease.

Epidemiology

Due to the rarity of the disease, the epidemiology is poorly understood with current figures based on old retrospective studies. Available literature suggests an incidence of 0.2-0.5% following penetrating trauma and 0.01% following intraocular surgery. Race, age and sex do not seem to be associated with increased incidence of disease (2). There is also evidence that SO has a genetic predisposition and is associated with Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4, HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQA1(3-4).

Mechanism and Etiology

Currently, the most widely accepted theory is that SO is caused by a delayed cell mediated immune response to retinal photoreceptor layer antigens (5). Penetrating trauma or surgery exposes these immunoprivileged antigens to the immune system, resulting in an autoimmune inflammatory response affecting both eyes. This theory is supported by immunohistochemical studies that identify a T cell mediated inflammatory response involving an early infiltration of CD4 helper T cell and laterinfiltration of CD8 cytotoxic T cell in the uveal tract of patients with SO (6). Therefore damage to one (exciting) eye results in a T cell mediated response that damages theother (sympathizing) eye. Dalen Fuchs nodules which are collections of macrophages or degenerated retinal pigment epithelium beneath the neuroretina canal so characteristically be seen (7). Notably, the pathophysiology of SO is similar tothat of Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome, with the major differentiator being involvement of the choriocapillaris in chronic recurrent VKH not seen in SO (8).

Clinical Presentation

Patients with SO classically present weeks to months after the sympathizing event with insidious onset of symptoms of uveitis such as photophobia, decreased visual acuity and pain. Presentation can be non-specific and hence a thorough history is vital in identifying the potential inciting injury.

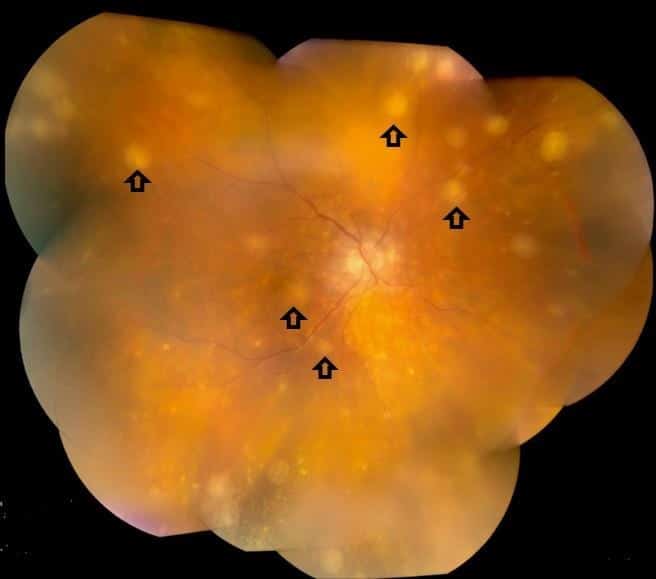

Clinical examination will show findings in line with granulomatous uveitis. Anterior segment findings can include mutton fat keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells or flare, cataract formation and posterior synechiae. The posterior segment may show signs of vitritis, choroiditis, optic nerve oedema, macular oedema, exudativeretinal detachment or Dalen-Fuchs nodules (9-10). Clinical findings of SO is normally limited to the eye but on rare occasions systemic symptoms of hearing loss, vitiligo and meningism may be present (11).

The main differential diagnosis of SO is VKH with similar ocular symptoms and examination findings. The main differentiating factor would be the history of ocular trauma and the absence of systemic symptoms. VKH is associated with a much higher rate or systemic symptoms such as headache, vitiligo, alopecia and poliosis(12). It is also important to identify and rule out infectious causes of uveitis such as tuberculosis and syphilis.

Investigations

The main ancillary procedures used to characterise and diagnose SO is ocular coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA). OCT can be utilised to identify, document and follow retinal oedema or detachment. This can be useful in not only the diagnosis but also monitoring response to treatment (13). FFA can be helpful in identifying areas of hyper or hypo-fluorescing spots which can correspond to serous retinal detachments or Dalen-Fuchs nodules (14).

Treatment

After excluding infective causes of uveitis, the mainstay of treatment has historically been with systemic corticosteroid therapy. Early administration of high dose corticosteroids seems to be linked with better visual prognosis. There is also evidence that early enucleation of the exciting eye results in better visual outcomes in the sympathizing eye but this is controversial (15-16). More recently, there has been consensus that immunomodulatory drugs such as Adalimumab can be considered for the management of SO (17).

Patients with SO need to be closely monitored and followed up to evaluate response to treatment.

Conclusion

SO is a rare but potentially devastating disease that should be considered in a patient presenting with bilateral granulomatous uveitis. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment is vital in ensuring the best visual prognosis of these patients.

References

1) Chu X, Chan C. Sympathetic ophthalmia: to the twenty-first century and beyond. Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection. 2013;3(1):49.

2) Arevalo J, Garcia R, Al-Dhibi H, Sanchez J, Suarez-Tata L. Update on sympathetic Ophthalmia. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology.2012;19(1):13.

3) Davis JL, Mittal KK, Freidlin V, Mellow SR, Optican DC, Palestine AG, et al. HLA associations and ancestry in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1137–42.

4) Kilmartin DJ, Wilson D, Liversidge J, Dick AD, Bruce J, Acheson RW, et al.Immunogenetics and clinical phenotype of sympathetic ophthalmia in British and Irish patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:281

5) Wong VG, Anderson R, O’Brien PJ. Sympathetic ophthalmia and lymphocyte transformation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72(5):960–966. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(71)91697-7

6) Chan CC, Benezra D, Rodrigues MM, Palestine AG, Hsu SM, Murphree AL,Nussenblatt RB. Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy of choroidalinfiltrates and Dalen-Fuchs nodules in sympathetic ophthalmia.Ophthalmology. 1985;3(4):580–590.

7) Goto H, Rao NA. Sympathetic ophthalmia and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1990;3(4):279–285. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199030040-00014.

8) Rao NA. Mechanisms of inflammatory response in sympathetic ophthalmia and VKH syndrome. Eye. 1997;11(Pt 2):213–216. doi:10.1038/eye.1997.54

9) Croxatto JO, Rao NA, McLean IW, Marak GE (1982) Atypical histopathologic features in sympathetic ophthalmia. A study of a hundred cases. Int Ophthalmol 4(3):129–135

10)Gupta V, Gupta A, Dogra MR. Posterior sympathetic ophthalmia: a single centre long-term study of 40 patients from North India. Eye. 2008;3(12):1459–1464.

11)Kilmartin DJ, Dick AD, Forrester JV. Sympathetic ophthalmia risk following vitrectomy: should we counsel patients? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;3(5):448–449.doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.5.448.

12)Yang P, Liu S, Zhong Z, et al. Comparison of Clinical Features and Visual Outcome between Sympathetic Ophthalmia and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease in Chinese Patients. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(9):1297-1305.doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.03.049

13) Chan RV, Seiff BD, Lincoff HA, Coleman DJ. Rapid recovery of sympathetic ophthalmia with treatment augmented by intravitreal steroids. Retina.2006;3(2):243–247. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200602000-00029

14) Damico FM, Kiss S, Young LH. Sympathetic ophthalmia. Semin Ophthalmol.2005;3(3):191–197. doi: 10.1080/08820530500232100

15)Reynard M, Riffenburgh R, Maes E. Effect of Corticosteroid Treatment and Enucleation on the Visual Prognosis of Sympathetic Ophthalmia. AmericanJournal of Ophthalmology. 1983;96(3):290-294.

16)Lubin J, Albert D, Weinstein M. Sixty-Five Years of Sympathetic Ophthalmia.Ophthalmology. 1980;87(2):109-121.

17)Okada A. Immunomodulatory Therapy for Ocular Inflammatory Disease: A Basic Manual and Review of the Literature. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2005;13(5):335-351.